DS 210 A1 - Programming for Data Science - Spring 2026

Welcome to DS 210 Section - Programming for Data Science in Rust.

This course builds on DS110 (Python for Data Science) by expanding on programming language, systems, and algorithmic concepts introduced in the prior course. The course introduces students to Rust, a compiled and high performance language. It also introduces students to important systems level concepts such as computer architecture, compilers, file systems, and using the command line.

Look at the course's syllabus and schedule for more details.

This website is for DS 210 section A1 (MWF), if you are looking for section B1 (TR), go here.

Previous Offerings

Course Schedule

This schedule is updated frequently. Please check the readings and exercises before each class.

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 19 | Jan 20 | Jan 21 Lecture 1: course overview Discussion 1: Rust & IDE setup | Jan 22 | Jan 23 Lecture 2: why Rust? Rust vs Python |

| Jan 26 Snow day - no class | Jan 27 | Jan 28 Lecture 3: shell & terminals Discussion 2: TBD HW 1 out: command line and Git | Jan 29 | Jan 30 Lecture 4: shell & terminals (2) |

| Feb 2 Lecture 5: TBD | Feb 3 | Feb 4 Lecture 6: TBD Discussion 3: TBD HW 1 due: command line and Git HW 2 out: Rust basics (1) | Feb 5 | Feb 6 Lecture 7: TBD |

| Feb 9 Lecture 8: TBD HW 2 due: Rust basics (1) HW 3 out: Rust basics (2) | Feb 10 | Feb 11 Lecture 9: TBD Discussion 4: TBD | Feb 12 | Feb 13 Lecture 10: TBD |

| Feb 16 Presidents day - no class HW 3 due: Rust basics (2) Proj 1 out: Vec | Feb 17 Lecture 11: TBD | Feb 18 Midterm 1 Discussion 5: TBD | Feb 19 | Feb 20 Lecture 12: TBD |

| Feb 23 Lecture 13: TBD Proj 1 (part 1) due: Vec | Feb 24 | Feb 25 Lecture 14: TBD Discussion 6: TBD | Feb 26 | Feb 27 Lecture 15: TBD |

| Mar 2 Lecture 16: TBD Proj 1 (part 2) due: Vec Proj 2 out: chatbot | Mar 3 | Mar 4 Lecture 17: TBD Discussion 7: Vec code review | Mar 5 | Mar 6 Lecture 18: TBD |

| Mar 9 Spring break - no class Proj 2 (part 1) due: chatbot | Mar 10 Spring break | Mar 11 Spring break - no class | Mar 12 Spring break | Mar 13 Spring break - no class |

| Mar 16 Lecture 19: TBD Proj 2 (part 2) due: chatbot | Mar 17 | Mar 18 Lecture 20: TBD Discussion 8: TBD | Mar 19 | Mar 20 Lecture 21: TBD |

| Mar 23 Lecture 22: TBD Proj 2 (part 3) due: chatbot Proj 3 out: client-server analytics | Mar 24 | Mar 25 Midterm 2 Discussion 9: chatbot code review | Mar 26 | Mar 27 Lecture 23: TBD |

| Mar 30 Lecture 24: TBD Proj 3 (part 1) due: client-server analytics | Mar 31 | Apr 1 Lecture 25: TBD Discussion 10: TBD | Apr 2 | Apr 3 Lecture 26: TBD |

| Apr 6 Lecture 27: TBD Proj 3 (part 2) due: client-server analytics Proj 4 out: Tic-Tac-Toe | Apr 7 | Apr 8 Lecture 28: TBD Discussion 11: client-server analytics code review | Apr 9 | Apr 10 Lecture 29: TBD |

| Apr 13 Lecture 30: TBD Proj 4 (part 1) due: Tic-Tac-Toe | Apr 14 | Apr 15 Lecture 31: TBD Discussion 12: TBD | Apr 16 | Apr 17 Lecture 32: TBD |

| Apr 20 Patriots day - no class Proj 4 (part 2) due: Tic-Tac-Toe | Apr 21 | Apr 22 Lecture 33: TBD No discussion | Apr 23 | Apr 24 Lecture 34: TBD |

| Apr 27 Lecture 35: TBD | Apr 28 | Apr 29 Lecture 36: TBD Discussion 13: Tic-Tac-Toe code review | Apr 30 | May 1 Study period - no class Proj 4 (part 3) due: Tic-Tac-Toe |

| May 4 | May 5 | May 6 Final Exam | May 7 | May 8 |

Homework, Mini Projects, and Exams

This is a list of the homework assignments, mini projects, and exams for DS 210 A1 - Spring 2026:

- Homework 1: command line and git basics due Feb 4

- Homework 2: Rust basics due Feb 9

- Homework 3: Rust basics (2) due Feb 16

- Midterm exam 1 (in class): Feb 18

- Basic Rust syntax

- Command line and git

- Mini project 1: memory managament - build your own vector

- Part 1: basic implementationdue Feb 23

- Part 2: doubling capacity and experimentationdue Mar 2

- Code reviewMar 4

- Mini project 2: AI chatbot application

- Part 1: ring buffer due Mar 9

- Part 2: basic chatbot due Mar 16

- Part 3: caching chatbot due Mar 23

- Code reviewMar 25

- Midterm exam 2 (in class): Mar 25

- Computer organization and memory

- Rust ownership and references

- Data structures

- Mini project 3: client-server data analytics

- Part 1: using remote procedure calls (RPCs) due Mar 30

- Part 2: using sockets due Apr 6

- Code reviewApr 8

- Mini project 4: Tic-Tac-Toe agents

- Part 1: 3x3 Tic-Tac-Toe due Apr 13

- Part 2: 5x5 Tic-Tac-Toe with heuristic due Apr 20

- Part 3: optimization and tournament due May 1

- Code reviewApr 29

- Final exam (12pm - 2pm; location TBD) May 6

- Course recap

- Parallelism and synchronization

- Code review and critique

- Experiment design

DS 210 A1 - Programming for Data Science

This course builds on DS110 (Python for Data Science) by expanding on programming language, systems, and algorithmic concepts introduced in the prior course. The course begins by exploring the different types of programming languages and introducing students to important systems level concepts such as computer architecture, compilers, file systems, and using the command line. It introduces Rust, a safe and high performance compiled language, and shows how to use it to implement and understand a number of fundamental data structures, algorithms, and systems concepts.

While DS110 focuses on writing small, standalone Python scripts for data science, DS210 aims to expose students to designing and implementing larger programs and software packages, as well as testing, optimizing, and evaluating these programs.

Prerequisites: CDS 110 or equivalent

Learning Objectives

By the end of this course students will:

- Be familiar with basics of computer organization and how it affects correctness and performance of programs, including the basic computer structure, memory management and safety, and basic concurrency and synchronization.

- Understand how to implement, evaluate, and optimize high performance code.

- Become more comfortable designing and implementing moderately complex software packages.

- Understand how to evaluate and improve the quality of code with respect to readability, maintainance, performance, and modularity.

- Learn basic data structures and algorithmic concepts, e.g., vectors, linked lists, stacks, and hashmaps.

Why are these concepts important?

Jobs/careers: Given the increasing competativness of the job market, it is crucial to have a strong technical background in building good quality and performant programs and software to acquire and succeed in data science, data engineering, and software engineering jobs at reputable employers. This course teaches fundemental concepts and practical skills crucial for such employers and jobs. Students who do not master the material in this course will struggle to succeed in such jobs (or even get their careers started).

Technical interviews: Technical interview almost always include coming up with an effective solution for a data structure or algorithmic problem and implementing it effectively in clean, good quality code. This course helps student practice this skill.

The CDS curiculumn: DS 210 plays an important role in the CDS curiculumn, with many higher-level courses depending on it as a pre-requisites. For many students, it is the only course where they will encounter computer organization and systems concepts that are nontheless crucial for their success in other practical-oriented upper level courses and practicums.

Student growth and technical background: A data scientist or engineer that does not understand the basics of how a computer works cannot effectively understand why their programs behave the way that they do. The material in this course will help students move past the stage where the data science tools they use are mystery boxes. Instead, students will have a greater understanding of how and why they work, and the behind-the-scenes reasons for why they are designed the way that they are. Thus, helping student use these tools (and learn new ones) more effectively.

Lectures and Discussions

A1 Lectures: Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays 12:20pm -1:10pm, WED 130 (2 Silber Way)

Section A Discussions:

- A2: Wednesdays, 1:25pm – 2:25pm, FLR 122 (808 Commonwealth Ave)

- A3: Wednesdays, 2:30pm – 3:20pm, IEC B10 (888 Commonwealth Ave)

- A4: Wednesdays, 3:35pm – 4:25pm, IEC B10 (888 Commonwealth Ave)

Note: There are two sections of this course, they cover similar materials, however, their schedules, homework, and discussion sections are different. They are not interchangeable. You must attend the lecture and discussion section you are register for!

Consistently attending and participating in both lectures and discussions is expected and constitute a sizable part of your grade in this course.

Course Content Overview

- Part 1: Why Rust and why should you care? Foundations: command line, git, and Rust basics syntax and features. (Weeks 1-3)

- Part 2: Core Rust concepts. Evaluating code quality and performance. (Weeks 4-5)

- Midterm 1 (~Week 5)

- Part 3: Memory management. Data structures and algorithms. (Weeks 6-10)

- Midterm 2 (~Week 10)

- Part 4: Advanced Rust. Parallelism and Concurrency. (~Weeks 11-13)

- Part 5: Data Science & Rust in Practice (~Weeks 14-15)

- Final exam during exam week

For a complete list of modules and topics that will be kept up-to-date as we go through the term, see the lectures schedule and the list of homework and exam deadlines.

Course Format

Lectures: our lectures will involve extensive hands-on practice. Each class includes:

- Interactive presentations of new concepts, including live coding and visualizations

- Small-group exercises and problem-solving activities

- Discussion and Q&A

Because of this active format, regular attendance and participation is important and counts for a significant portion of your grade (15%).

Discussions: our TAs will work with you on technical interview-style programming exercises in small groups, provide homework support, and will be used occasionally for oral code reviews for homework solutions.

The discussions count towards the attendance portion of your grade.

Pre-work: we will generally assign short, light readings or small exercises ahead of class to help you prepare for in-class activities, and may include short quizes (graded to completion) to help us keep track of the class's progress. We will also periodically ask for feedback and reflections on the course between lectures.

Homework/Mini Projects: a key goal of this course is to have you write significant code, both in size and complexity. The only way to master programming is with practice. You can find a tentative schedule of our assignments and their deadlines at this page.

These are split into these categories. Together they constitute 40% of your grade:

-

Homework: we will have small weekly assignments for the first 4 weeks. These will help you get set up and familiarize yourself with the tools we will use throughout the course.

-

Mini projects: after the first 4 weeks, the course will move towards mini projects. There are group assignments for groups of 2-3 students. They span multiple weeks and contain multiple parts that build on each other, each part will be due one week at a time.

-

Code reviews/oral examination: We will also conduct code reviews/oral examination with every group about their solution during the disucssion section immediately following their due date. This process will mimic code review practices in industry and offer students feedback about how they improve their solutions and programming skills. They also serve as a check to ensure students only hand in code they have written (and understood) themselves and that group members are collaborating effectively.

-

Corrections/feedback: Students will have the option to submit revised solutions in up to two mini projects of their choosing after their code reviews. This allows them to address feedback given by the teaching staff during review, earning up to 50% of the missed grade. This mimics the process for improving, approving, and merging code in the industry.

Find more details about the mini projects, code reviews, and their policies here.

Exams Two midterms and a cumulative final exam covering the concepts we see in class and in the homework and mini projects. They also include short hand-coding problems (which we will practice in class!). The exams constitute 30% of the final grade.

The course emphasizes learning through practice, with opportunities for corrections and growth after receiving feedback on assignments.

Time Commitment

In a typical week, students are expected to attend the three lectures and the disucssion section (~3.5 hours) and allocate 1-1.5 hours for class pre-work. This is a coding heavy course, and students will need to allocate 7-8 hours per week on average to work on the assignment homework and mini projects.

The best way to practice for the exams is by doing the homework and mini projects and engaging in the lecture pre-work and in-class activities. However, we will adjust the assigned workload during the week of exams to allow students some time to review the lecture notes and material, if they so wish.

In total, we expect students to allocate 12-13 hours per week to DS 210 between attending lectures, discussion, and assignments.

This is a programming heavy course that push students to practice and improve their programming skills. We believe this is crucial to the student's careers, growth, and job prospects. In return, the teaching staff commits to dedicating themselves to helping the students in and outside of class, and providing them with feedback, resources, and guidance to ensure they succeed.

We are on your side as you battle programming, computers, and the Rust compiler.

A1 Course Staff

Section A1 Instructor: Kinan Dak Albab

Email: babman@bu.edu

Office hours: Mondays 11:00am - 12:00pm and Fridays 1:30pm - 2:30pm @ CDS 1336

If you want to meet but cannot make office hours, send a private note on Piazza with at least 2 suggestions for times that you are available, and we will find a time to meet.

A1 TAs

-

Taishan Chen (utallow@bu.edu)

Office Hours: TBD -

Zach Gentile (zgentile@bu.edu)

Office Hours: Mondays 2:00pm - 4:00pm, location TBD

A1 CAs

-

Emir Tali (etali@bu.edu)

Office Hours: Wednesdays 11:30am - 1:20pm, location TBD -

Mattew Morris mattmorr@bu.edu)

Office Hours: TBD -

Kesar Narayan (kesar@bu.edu)

Office Hours: TBD -

Lingjie Su (sljleo@bu.edu)

Office Hours: TBD

Course Websites and Material

- Syllabus (this document)

- Interactive lecture notes

- Schedule page

- Homework, Mini project, and exam deadlines

Piazza

- Announcements and additional information

- Questions and discussions

- Code from lectures and discussion sections

- In-class coding exercises and their solutions

Gradescope

- Homework and in class activities submission

- Gradebook

- Programming exercises and challenges

- The standard for practicing for technical interviews!

Other Resources

The Rust Language Book

by Steve Klabnik, Carol Nichols, and Chris Krycho, with contributions from the Rust Community

This is a great resource that goes over the various Rust languages features in detail. It starts with the basics (variables, types, and loops) and ends with more advanced features (concurrency, unsafe).

Brown University Experimental Rust Course

This is a fork of the official Rust Language Book with integrated short quizzes and language visualizations.

- Website: https://rust-book.cs.brown.edu/index.html

- Repo: https://github.com/cognitive-engineering-lab/rust-book

Grading, Homework, and Exams

Grade breakdown

Your grade will be determined as:

- 40% assignments

- 3 homeworks in the begining of the semster (5%)

- 4 mini projects (35%)

- 15% attendance: includes lectures and discussion sections.

- 15% final exam

- 10% mid term 1

- 10% mid term 2

- 10% pre-work, surveys, and in-class activities

We will use the standard map from numeric grades to letter grades (>=93 is A, >=90 is A-, etc). For the midterm and final, we may add a fixed number of "free" points to everyone uniformly to effectively curve the exam at our discretion - this will never result in a lower grade for anyone.

We will use gradescope to track grades over the course of the semester, which you can verify at any time and use to compute your current grade in the course for yourself.

Some mini projects will offer opportunities for extra credit which provide a suplement on top of the grades from the above (i.e., allow students to get more than 100% or make up for lost work).

Assignments Grading and Policies

Mini projects

Our 4 mini projects are graded equally as follows:

- 60% correctness and performance: whether your code passes our tests within the allocated time.

- 40% code reviews / oral examination: include code quality, collaboration, and analysis/reflection.

You will get partial credit for solutions that do not pass all the tests or that take longer than the allocated time. This partial credit is proportional to how far your solution is from one that meets our tests and performance. You may receive some partial credit for code that does not compile or otherwise fail to pass any of the tests, provided that it demonstrates some conceptual understanding of the material.

Group work

The 3 homeworks are individual work. Our mini projects are for groups of 2-3 students.

All students in a group must be registered for the same disucssion section.

We expect students to contribute equally to these projects, and provide some guidelines for how they can split the work amongs themselves. Groups with drastically unequal contribution between their members will receive grade penalties.

All students in the group will share the correctness and performance grade component, but they will receive individual grade for the code reviews.

Code reviews

We will have 4 code reviews in total, one for each mini project. We will hold the code reviews during the discussion sections immediately following the mini project deadline. We will review late submissions at their current state, provided they are suffiently near completion. If you have no code or progress to show during code review, you will receive a 0 on that mini project.

Code review format: Each group will have their own code review during the discussion section they are registered for (roughly 15 minutes long). The reviewer will be the instructor or one of the TAs.

Code review contents: The code reviews will provide you with feedback about the design of your code and any potential issues. The review will include verbal questions directed at the entire group, and specific questions for individual students. The review will go over your code and your commit history. It will also provide you with feedback.

We will ask students to explain certain code blocks, justify their design or approach, or compare it with other hypothetical approaches. They will also contain reflection questions that ask you to draw conclusions or highlight lessons you learned from working on the assignment.

Absences: All members of a group need to be present for their code review. A group may request an alternative time for a code review provided reasonable justification, and we will work with them to find a suitable arrangement, e.g., in office hours.

We ask that students give us at least 2 days notice before requesting rescheduling. Missing code review without a document execused or without giving prior notice may result in 0 for that mini project.

Corrections and resubmissions

Students will have the chance to resubmit their solutions for up to two mini projects of their choosing after the code review. The deadline for resubmission is Mondays, at 11:55pm.

Students can use the feedback they received in the code review to improve their code, e.g., make it pass all the tests cases, execute faster, or have a better design and overall code quality. This allows them to earn up to 50% of any grades they missed in their original submission.

Online Resources and AI Use

Wholesale use of AI in the homework and mini projects is forbidden. We define wholesale to mean asking AI to generate chunks of code, such as entire functions, structs, or complex multi-line code blocks.

We encourage you not to mindlessly use AI to help with your assignment. This can lead to over reliance on AI and defeat the purpose of the assignment: for you to practice your coding skills. Limited use of AI, e.g., to find particular API calls, is allowed, provided you are able to explain your code, design choices, and reason about the decisions you made during code review. The same applies to other resources, such as stackoverflow. You will need to document such code with a comment and provide a link to the online resource or relevant prompts you used.

AI Use Document: You will be required to submit a short document with each assignment describing how you used AI, if at all. We will confirm your understanding of the code, and whether any AI use was within acceptable parameters in the code reviews.

Over reliance on AI: If you are unable to adequately explain your code or answer questions about it in code review due to over-reliance on AI consistent with your AI use document, you may lose a significant portion of your code review portion of the grade.

Academic dishonesty: If you fail to honestly report your use of AI or online resource and we confirm this via our code review, you will receive 0 on that mini project, and your final grade in the course will be capped at a B. A repeat violation will result in an automatic F. We may refer eggreious cases to appropriate CDS and BU committees.

Due date and late submission

Our homework and mini projects are generally due on Mondays, 11:55pm. Students have the option to submit up to two days late for a maximum of 80% of the assignments grade.

Attendance

We will track attendance in lectures via in class polls. These polls track the location of the students to ensure they are physically at class.

We understand that unexpected circumstances can happen: students may miss up to 3 lectures and 1 discussion section without having to provide an execuse

We will accomodate documented absences within reason and inline with BU's policies and guidelines, but may ask for official documentation.

Course Policies

Exams

The final will be during exam week, date and location TBD. The two midterms will be in class during normal lecture time.

If you have a valid conflict with a test date, you must tell us as soon as you are aware, and with a minimum of one week notice (unless there are extenuating circumstances) so we can arrange a make-up test.

If you need accommodations for exams, schedule them with the Testing Center as soon as exam dates are firm. See below for more about accommodations.

Deadlines and late work

Homeworks and mini projects will be due on the date specified in gradescope.

If your work is up to 48-hours late, you can still qualify for up to 80% credit for the assignment. After 48 hours, late work will not be accepted unless you have made prior arrangements due to extraordinary circumstances.

Collaboration

Mini projects are group based, and members of a group are expected to contribute equally to the solution.

You are free to discuss problems and approaches with other students beyond your group, but must do your own coding. If a significant portion of your solution is derived from someone else's work (your classmate, a website, a book, etc), you must cite that source in your writeup.

You must also understand your solution well enough to be able to explain it during code review. You will not be penalized for using outside sources as long as you cite them appropriately and meet the code review expectations.

Academic honesty

You must adhere to BU's Academic Conduct Code at all times. Please be sure to read it here.

In particular: cheating on an exam, passing off another student's work as your own, or plagiarism of writing or code are grounds for a grade reduction in the course and referral to BU's Academic Conduct Committee.

If you have any questions about the policy, please send us a private Piazza note immediately, before taking an action that might be a violation.

AI use policy

You are allowed to use GenAI (e.g., ChatGPT, GitHub Copilot, etc) to help you understand concepts or lecture notes.

For homeworks and mini projects, you are only allowed to use AI in limited, piece-meal fashion, e.g., to search for a particular API, or explain a very specific error you are encoutering. You should understand that this may help or significantly impede your learning depending on how you use it.

If you use GenAI for an assignment, you must cite what you used and how you used it (for brainstorming, autocomplete, generating comments, fixing specific bugs, etc.). You must understand the solution well enough to explain it during code review.

If you fail to report how you used GenAI for an assignment in adequate detail, or if you are unable to explain the basics of the solution in code review, this may result in a 0 for that assignment. A serious, repeat violation will earn you an automatic F in the course.

Your professor and TAs/CAs are happy to help you write and debug your own code during office hours, but we will not help you understand or debug code that generated by AI.

For more information see the CDS policy on GenAI.

Attendance and participation

Since a large component of your learning will come from in-class activities and discussions, attendance and participation are essential and account for 10 and 15% of your grade, respectively.

Attendance will be taken in lecture through polls which will open at various points during the lecture. If you miss such a poll (e.g., due to being significantly late to class), that will count as an abscense. The polls use a custom made website that confirms your location. Attempting to submit such a poll from a different location (e.g., your home) will be detected and may constitute an instance of academic dishonesty/cheating.

Understanding that illness and conflicts arise, up to 3 absences are considered excused and will not affect your attendance grade.

In most lectures, there will be time for small-group exercises, either on paper, GitHub, or gradescope. To receive participation credit on these occasions, you must identify yourself on paper or in the repo/gradescope submission. These submissions will not be graded for accuracy, just for good-faith effort.

Occasionally, we may ask for volunteers, or may cold call students randomly to answer questions or present problems during class. You will be credited for participation/in-class activities for such contributions.

Absences

This course follows BU's policy on religious observance. Otherwise, it is generally expected that students attend lectures and discussion sections. If you cannot attend classes for a while, please let me know as soon as possible. If you miss a lecture, please review the lecture notes on this website before the next class.

Accommodations

If you need accommodations, let us know as soon as possible. You have the right to have your needs met, and the sooner you let us know, the sooner we can make arrangements to support you.

This course follows all BU policies regarding accommodations for students with documented disabilities. If you are a student with a disability or believe you might have a disability that requires accommodations, please contact the Office for Disability Services (ODS) at (617) 353-3658 or access@bu.edu to coordinate accommodation requests.

If you require accommodations for exams, please schedule that at the BU testing center as soon as the exam date is set.

Re-grading

You have the right to request a re-grade of any homework or test. All regrade requests must be submitted using the Gradescope interface. If you request a re-grade for a portion of an assignment, then we may review the entire assignment, not just the part in question. This may potentially result in a lower grade.

Corrections

You are welcome to submit corrections on your mini projects. This is an opportunity to take the feedback you have received during code review, reflect on it, and then demonstrate growth. Corrections involve submitting an updated version of the mini project alongside the following reflections in a document:

- A clear explanation of the issues or feedback

- What misconception(s) led to it

- An explanation of the correction

- What you now understand that you didn't before

After code review, you will have until the following Monday to submit corrections. You can only submit corrections on a good faith attempt at the initial submission (not to make up for a missed or severly incomplete assignment).

Satisfying this criteria completely for any particular mini project will earn you back up to 50% of the points you originally lost (no partial credit).

DS210 Course Overview

Lecture 1: Wednesday, January 21, 2026

This lecture introduces DS 210 A1: Programming for Data Science, covering course logistics, academic policies, grading structure, and foundational concepts needed for the course.

Overview

This course builds on DS110 (Python for Data Science). That, or an equivalent is a prerequisite.

We will spend the bulk of the course learning Rust, a modern, high-performance and more secure programming language. While running and using Rust, we will cover important foundational concepts and tools for data scientists and programmers:

- Tools

- Shell commands

- Git version control

- Computer architecture and systems

- Overview of CPU architectures and instruction sets

- Memory layouts and memory management

- Basic parallelism and synchronization

- Algorithmic foundations

- Basics of runtime analysis and big O notation

- Basic data structures (vectors, linkedlists, hashmaps) and their uses

Why is it important for data science students to learn these concepts?

- It is important to have a strong technical background in effective programming for your future careers. This includes understanding how the computer works, and how that affects the performance and correctness of your programs.

- You need knowledge of data structures and algorithms and to be able to put that knowledge into clean, concise code to succeed at technical interviews.

- Many upper courses in the CDS curiculumn require a good background in the topics we will learn in 210.

- This course and the handson programming practice are an opportunity for technical and professional growth.

Consult the syllabus for detailed information about the course objectives.

New This Semester

We've made some significant changes to the course based on observations and course evaluations.

- Homework/mini projects: more and larger mini projects that focus on re-enforcing the systems and algorithmic concepts from class and give you more experience with interemediately complex programs.

- Code review sessions: to provide you with feedback about your code, mimic industry code review processes, and ensure you carry out the work yourself rather than outsource your work and thinking to AI.

- Less emphasis on exams: the exams will focus on the concepts we learn in the course and less on pen-and-paper coding, as well as a smaller portion of your overall grade.

Question: What have you heard about the course? Is it easy? Hard? Do these changes above align with your impressions?

Course Timeline and Milestones

The course is roughly split into these units:

- Part 1: Foundations (command line, git) & Rust Basics (Weeks 1-3)

- Part 2: Core Rust Concepts (Weeks 4-5)

- Midterm 1 (~Week 5)

- Part 3: Memory management and data structures. (Weeks 6-10)

- Midterm 2 (~Week 10)

- Part 4: Advanced Rust. Parallelism and Concurrency. (~Weeks 11-13)

- Part 5: Data Science & Rust in Practice (~Weeks 14-15)

- Final exam during exam week

Additionally, the course will have weekly homework and miniprojects, usually due on Mondays. Check the deadlines page.

Course Format

Lectures with hands on exercises and active discussion. Attendance is required.

Discussions will review and reinforce lecture material and provide further opportunities for hands-on practice. We will allocate specific discussion sections for code reviews. Attendance is also required.

Pre-work will be assigned before most lectures to prepare you for in-class activities. These are typically short readings followed by a short quiz.

Homeworks and Mini projects are the key to learning the material in this course and to getting a good grade. They will proceed at a weekly pace. The first 3 homeworks are smaller, individual assignments to help you get familiar with the basics. The 4 mini projects are longer, group assignments to help you practice writing more complex code.

Exams 2 midterms and a cumulative final exam covering the concepts we learn in class.

Full details here.

Course Websites

You have been added to Piazza, we will also add you to Gradescope.

-

Piazza:

- Announcements and additional information

- Questions and discussions

-

Gradescope:

- Homework

- Gradebook

Grading and Policies

Grade distribution:

- 40% homework and mini projects

- 15% attendance (lectures and disucssion sections)

- 15% final exam

- 10% mid term 1

- 10% mid term 2

- 10% participation, pre-work, and in class activities

Important course and grading policies:

- code reviews for mini projects

- corrections and resubmissions for mini projects

- late submissions

- We encourage you to not use AI during your mini projects work, but if you must, you need to follow our

AI use policy

- You must report your use of AI and online resources along your submission

- If we judge that you over-relayed on AI given what you reported (e.g., during code reviews), we will deduct grades appropriately

- If we judge that you did not honeslty report AI use, you will receive a 0 for the mini project. A repeat violation is an automatic F.

- Other course policies: exams, collaboration, abscenses, accommodations.

We are not trying to be strict around AI-use for no reason. Instead, we believe this is necessary to ensure you get proper programming practice and truly learn this material. Given our policies and justification, do you feel like this policy is reasonable? Do you agree with it? Do you feel it is too restrictive?

Why Rust?

Lecture 2: Friday, January 23, 2026

Code examples

A common question we get from students is why did we chose to use Rust for this course instead of a different language? Why not continue with Python since it was used in DS 110?

It is important for us to explain our rational in some detail, and demonstrate to you the motivation behind these decisions. Throughout the course, you will struggle with some Rust-specific concepts and idiosyncrasies. We want you to understand that there is a reason you have to put up with (and overcome) all the hurdles of learning a new languages and in dealing with the Rust syntax, compiler, and borrow checker.

Why learn a new programming language? Why not continue to use Python?

Learning a second programming language builds CS fundamentals and teaches you to acquire new languages throughout your career.

Importantly, it also helps you distinguish what is an inherent property of how computers or algorithms work, and what is simply an incidental design decision, implementation choice, or a convention from a particular programming language ( and why that language made these choices, which often has deep and interesting justifications).

Example 1: What do we mean by an incidental choice?

Consider the following Python code:

print('hello world!')

We are all familiar with what this code does. However, nothing in it is particularly insightful about the essence of computers

or programming or even necessary given how they work. The fact that printing uses the word print is incidental. Other languages use

a different word for it, e.g., println in Rust, cout in C++, or console.log in Javascript.

In Python 3, printing is a function call, as evident by the paranthesis following print above. But it does not have to be this way:

in Rust, it is a macro (as we will see later), and even in Python 2, you could print using print "hello world".

Finally, Python does not really distinguish between " and ', but other languages, like Rust, do!

Example 2: Diving deeper into good and bad design choices

Consider the following Python code:

x = 2

y = '3'

print(x + y)

What is the output of running this code?

The above code produces a runtime error when run:

TypeError: unsupported operand type(s) for +: 'int' and 'str'

Is this the result of a fundemental aspect of how computers work? Not really. In fact, other languages similar code will have different behaviors.

In Javascript and Java, 2 + "3" results in "23"! These languages implicitly upgrade 2 to a string. Interestingly, in Javascript, 2 * "3" give 6, but not in Java!

If you were responsible for designing your own language. What alternative behaviors would you consider for

2 + '3'?

Some of your answers:

- "23"

- 5

- an error only if the string is truly a string, e.g.,

2 + 'hello', and 5 otherwise.

Some other answers we think would not be good:

- 0 or the empty string

- 5 for

2 + '3'but2hellofor2 + 'hello' - The number 23 (as a number, not a string).

It seems like there is a range of answers that are acceptable/somewhat reasonable, and a range of clearly unreasonable answers. What are the criteria that distinguish the two?

- Whether the choice reflects our natural/intuitive expectations as humans/programmers

- Whether the choice is confusing or has many corner cases

- Whether the choice results in silent failures if the program is executed that are hard to debug

Example 3: What are the tradeoffs at play when looking at competing choices

Consider the following Python code:

if 10 > 0:

x = 5

print(f"hello world {x}")

The below Rust code is equivalent:

fn main() { if 10 > 0 { let x = 5; println!("hello world {x}"); } }

Running both pieces of code (e.g., using the Rust playground) reveals

that they both produce identical output: hello world 5.

What are the most visible differences between the two code snippets

- The Rust code is contained within a function whose name is

main. - Python uses

:and indentation, Rust uses{and}. - Python delimits statement with new lines, Rust uses

;. - Variable declaration looks different, python does not distinguish from initial variable declartion and changing it in the future, Rust does by requiring initial declartion use

let.

We will understand what (1) and (4) mean later in the course. Let's focus on (2) and (3).

The following code is valid in Rust, however the same style in Python would not work: (a) the code is not indented properly, and (b) multiple statements share the same line.

fn main() { if 10 > 0 { let x = 5; println!("hello world {x}"); } }

Which do you prefer?

- Some of you prefer Python's style. Reasons include:

- being easier to read

- looking nicer and shorter (no

mainfunction) - you are already more familiar with Python: that code feels more natural

- Others prefer Rust:

- no issues with indentation (e.g., mixing spaces and tabs): these are a major headache when writing Python code

So, both approaches have nice things (and not so nice things). What dimensions are at odds here?

How nice the code looks and how easy it is to read vs how easy it is to write! E.g., indented code looks nicer

and shorter than code with { and }, but dealing with spaces and tabs is a headache while writing the code.

We call the first readability and the second writability. Sometimes these are subjective, sometimes they are less so.

We will see many more examples later.

Okay, you convinced us that we should learn a second language. Why Rust specifically?

Rust is a compiled language! It is very fast! It is also very different from Python!

What about other compiled and fast languages, like C++?

Compared to C++, Rust offers two important advantages:

Memory safety: Rust lets you see how data structures work in memory and manage your own memory, while reducing the risk of making various memory-related mistakes (e.g., a lot of the C/C++ headaches)

Strong type system: Rust has a strong type system that helps programmers writing Rust code ensure their programs are correct, memory safe, and type safe. We will understand what that means in the future.

In other words, the Rust compiler gives you errors and hints about your code to help you write code correctly, rather than allow you to write code any way you want, and then have to deal with fixing it when you encounter various errors during runtime.

Furthermore, Rust is experiencing growing adoption in industry and academia a like. This spans many fields, from low-level systems programming (e.g. the Linux kernel), software engineering, to data science and scientific computing!

We will investigate these notions in more depth later.

Rust, The Rust Compiler, and Speed

A big reason for why we want to teach you a compiled language, and specifically Rust, is that it is fast. But how fast is Rust (or compiled languages in generaly) you may ask.

Consider our very first, proper code example.

In this example, you can see two equivalent pieces of code in Rust and Python. The code first creates a list with many numbers (10 million numbers!), then sums all these numbers using a simple loop.

In the code, we measure the elapsed time between the start and end of that loop. In other words, the time that it takes to sum up the 10 million numbers.

First, we run the python code using cd src && python3 example.py. On my machine, the sum takes ~310ms. This is impressive! Imagine how long it would take

you, a human, to add up 10 million numbers.

Next, we run the rust code using cargo run. On my machine, the result takes 30ms. That is a 10x improvement! In other words,

if you were a company in the business of adding numbers (which is more or less what all the big AI companies do), you just cut down

your compute costs by a factor of 10! Big savings!

But wait. It gets better. We can ask Rust (specifically, the Rust compiler) to automatically optimize our code as much as it can using

cargo run --release. Now, the result takes ~1.5ms an impressive 200x speedup, or alternatively, a 200x reduction in compute costs.

BIG SAVINGS.

REALLY REALLY BIG SAVINGS.

What is a compiler? Why is it fast?

The content of the python file example.py is human-readable (some may disagree). It contains things like comments, variables with intelligible names, among other things.

Importantly, it is not written in a computer's native tongue: the ol' zeros and ones.

Notice how we ran the python code. We first type in the python3 command, then give it the name of the file we want to run. The python3 command is a translator: it is

responsible for reading out the file one line at a time, and translating it to the computer as it goes through it, telling the computer what to do.

This is a lot like when you watch a live TV speech in a foreign language: the TV station super imposes the voice of a live interpreter, that translates every sentence from the speaker's

language to English, allowing us to understand what the speaker says, but, often at a noticable delay.

The python3 command does exactly that (which is why it is infact called the Python interpreter), except the delay it introduces is even more significant (in relative terms), thus causing slower execution of code.

Rust instead does not have an interpreter, it is a compiled language. We can see how that operates using the following commands in our example code above:

# This compiles (or builds) but does not run the code

cargo build

# This takes us to the folder where the compiler produces the compiled code

cd target/debug/

# The compiled code is in a file called example

# This runs it

./example

You can see that our Rust code, once compiled, can be run directly, without any other commands: there are no interpreters!

Furthermore, we can print the contents of the compiled file. Note that it is not human-readable at all! This is all in zeros and ones, in the computer's native tongue.

# This takes us to the folder where the compiler produces the compiled code

cd target/debug/

# print the content of the compiled file

cat ./example

Finally, cargo run is simply a helpful shortcut that first compiles the code, then runs the compiled code.

Rust lets us get more visibility into how the computer works

Look at our second code example:

rows.rs and columns.rs are almost identical. Both create a large matrix of dimensions 10,000x10,000 (100 million elements) and sum all its elements

while timing the duration required for the sum.

The one difference is that rows.rs goes through the matrix one row at a time, starting from the first row. While the columns.rs goes one column at a time,

starting from the left most column.

Both add the same number of elements (100 million), so it stands to reason that they will take a similar amount of time. Let us see if that is the case:

cargo run --bin rows # runs rows.rs

cargo run --bin columns # runs columns.rs

On my machine, there is a noticeable difference: columns.rs is roughly 3x slower than rows.rs! Why?

It turns out this difference is entirely related to how the computer works, and not the algorithmic nature of either code (which is similar). Specifically, it has to do with how the CPU in a computer fetches the numbers from its memory (i.e., RAM), and how the numbers inside the matrix are placed in that memory. We will look at the details of computer memory and its structure later.

Key takeaway: the important lesson is that we need to understand how the computer works to inform us in how to write the most efficient formulation of our desired program.

Shell & Terminals

Lecture 3: Wednesday, January 28, 2026, and

Lecture 4: Friday, January 30, 2026

Every movie with hackers

The matrix had a legit terminal though

What is the terminal?

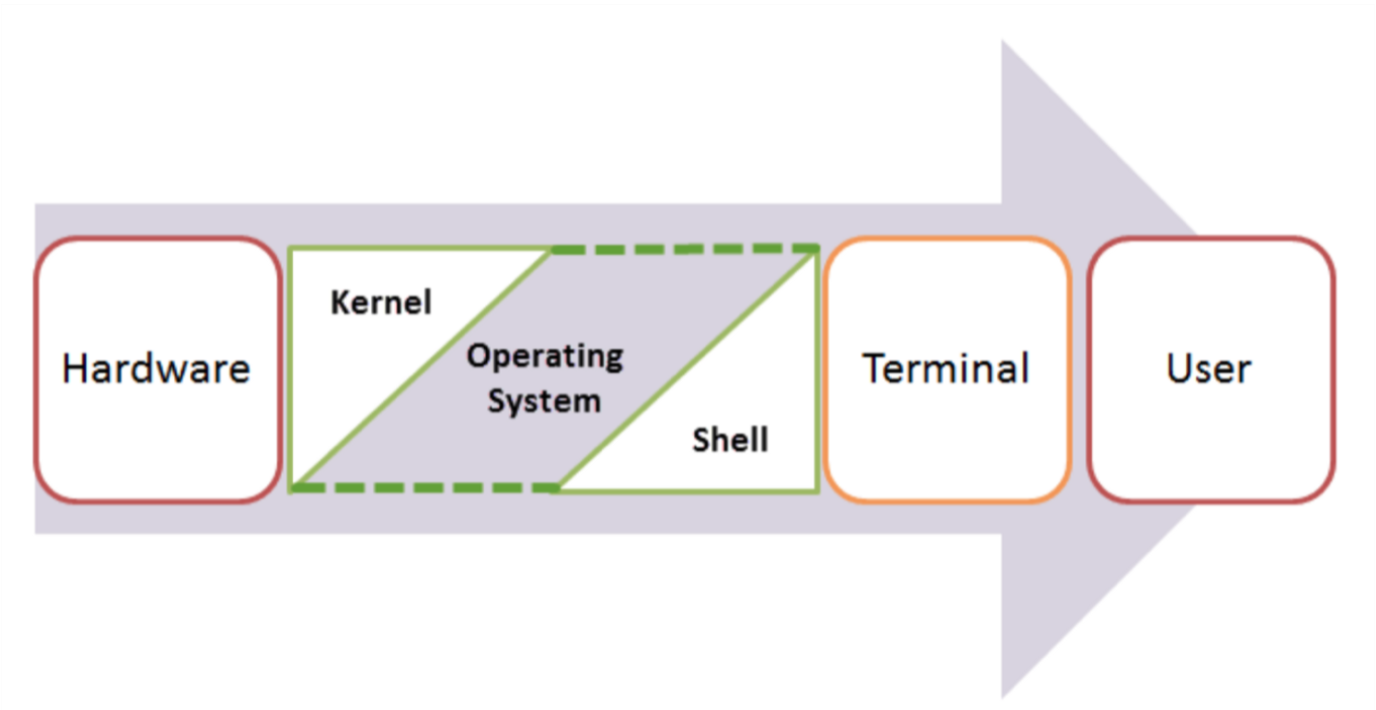

Shell, Terminal, Console, Command line... too many words?

- The command line is the interface where you type commands to interact with your computer.

- The command prompt is the character(s) before your cursor that signals you can type and can be configured with other reminders.

- The terminal or console is the program that opens a window and lets you interact with the shell.

- The shell is the command line interpreter that processes your commands. (You might also encounter "a command line" in text-based games)

Terminals are more like applications and shells are more like languages.

Some famous Terminals:

- Terminal (macOS)

- iTerm2 (macOS)

- GNOME Terminal (Linux)

- Konsole (Linux)

- Command Prompt (Windows)

- PowerShell (Windows)

- Git Bash (Windows)

Famous Shell interpreters:

- Bash (Bourne Again SHell) - most common on Linux and macOS (Kinan's favorite)

- Zsh (Z Shell) - default on modern macOS

- Fish (Friendly Interactive SHell) - user-friendly alternative

- Tcsh (TENEX C Shell) - popular on some Unix systems

- PowerShell - advanced shell for Windows

We often use all these words interchangeably in speech:

- "Open your terminal"

- "Type this command in the shell"

- "Run this in the command line"

- "Execute this in your console"

What is this all good for?

Lightning fast navigation and action

# Quick file operations

ls *.rs # Find all Rust files

grep "TODO" src/*.rs # Search for TODO comments across files

wc -l data/*.csv # Count lines in all CSV files

Question: How would you to this "manually"?

It's how we're going to build and manage our rust projects

# Start your day

git pull # Get latest code from GitHub (today's discussion sections)

# ... code some features ...

cargo run # Demo your new feature

cargo test # run your tests

git add src/main.rs # Stage your changes

git commit -m "Add awesome feature" # Save your work

git push # Share with the team

For when your UI just won't cut it

Confused by "invisible files" and folders?

ls -la

Need to find a file where you wrote something a while ago?

grep -r "that thing I wrote 6 months ago"

Modify lots of files at once?

# Rename 500 photos at once

for file in *.jpg; do mv "$file" "vacation_$file"; done

# Delete all files older than 30 days

find . -type f -mtime +30 -delete

"Why is my computer fan running like it's about to take off?"

df -h # See disk space usage immediately

ps aux | grep app # Find that app that's hogging memory

top # Live system monitor

In other words, the command line provides:

- Speed: Much faster for repetitive tasks

- Precision: Exact control over file operations

- Automation: Commands can be scripted and repeated

- Remote work: Essential for server management

- Development workflow: Many programming tools use command-line interfaces

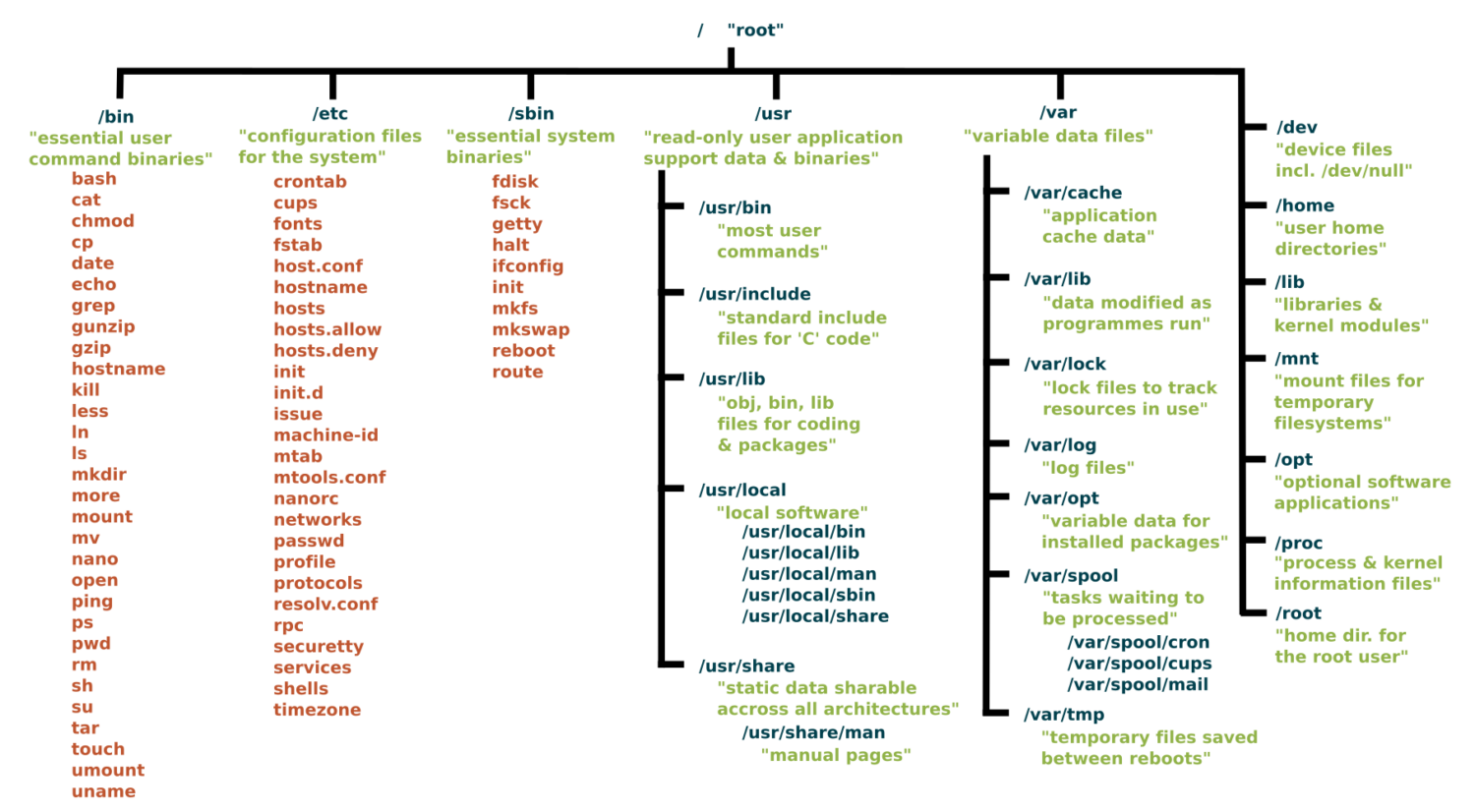

The file system and navigation

Everything starts at the root

Root Directory (/):

In Linux, the slash character represents the root of the entire file system.

(On a Windows machine you might see "C:" but on Linux and MacOS it is just "/".)

(We'll talk more about Windows in a minute)

Key Directories You'll Use:

/ # Root of entire system

├── home/ # User home directories

│ └── username/ # Your personal space

├── usr/ # User programs and libraries

│ ├── bin/ # User programs (like cargo, rustc)

│ └── local/ # Locally installed software

└── tmp/ # Temporary files

Navigation Shortcuts:

~= Your home directory.= Current directory..= Parent directory/= Root directory

Let's take a look / basic navigation demo

Demo time! First let's look at the command prompt...

Maybe half of your interactions with the shell will look like:

pwd # Print working directory

ls # List files in current directory

ls -a # List files including hidden files

ls -al # List files with details and hidden files

cd directory_name # Change to directory

cd .. # Go up one directory

cd ~ # Go to home directory

Tips:

- Use

Tabfor auto-completion (great for paths!) - Use

Up Arrowto access command history - Try

control-cto abort something running or clear a line - You can't click into a line to edit it, use left/right arrows (or copy-paste)

What's going on here?

The command line takes commands and arguments.

ls -la ~

The grammer is like a command in English: VERB (NOUN) ("eat", "drink water", "open door")

ls is the command, -la and ~ are arguments.

Flags / Options

Special arguemnts called "options" or "flags" usually start with a dash - and can be separate or combined. These are equivalent:

ls -la

ls -al

ls -a -l

ls -l -a

BUT they typically need to come before other arguemnts:

ls -l -a ~ # works!

ls -l ~ -a # does not work

Winblows (or is it Windows?)

If you use Windows, I am sorry for you.

macOS and Linux are both built on top of Unix, so they share many similarities.

Windows is entirely different

dirinstead oflscopyandmoveinstead ofcpandmv

Thankfully, Windows decided to support the same language as Unix, e.g. via PowerShell and the Linux subsystem for Windows.

We strongly recommend Windows users install a terminal with

bashso we can speak the same language. Git comes with a Git Bash terminal built in!

One thing is unavoidable: different paths

/vsC:\Users\(vote for which is a back slash!)- This incompatibility has caused more suffering than metric vs imperial units.

Essential Commands for Daily Use

The rest of the 80% of bash commands you will mostly ever use

Demo time!

mkdir project_name # Create directory

mkdir -p path/to/dir # Create nested directories

touch notes.txt # Create empty file

echo "Hello World" > notes.txt # Overwrite file contents

echo "It is me" >> notes.text # Append to file content

cat filename.txt # Display entire file

head filename.txt # Show first 10 lines

tail filename.txt # Show last 10 lines

less filename.txt # View file page by page (press q to quit)

nano filename.txt # Edit a file

cp file.txt backup.txt # Copy file

mv old_name new_name # Rename/move file

rm filename # Delete file

rm -r directory_name # Delete directory and contents

rm -rf directory_name # Delete dir and contents without confirmation

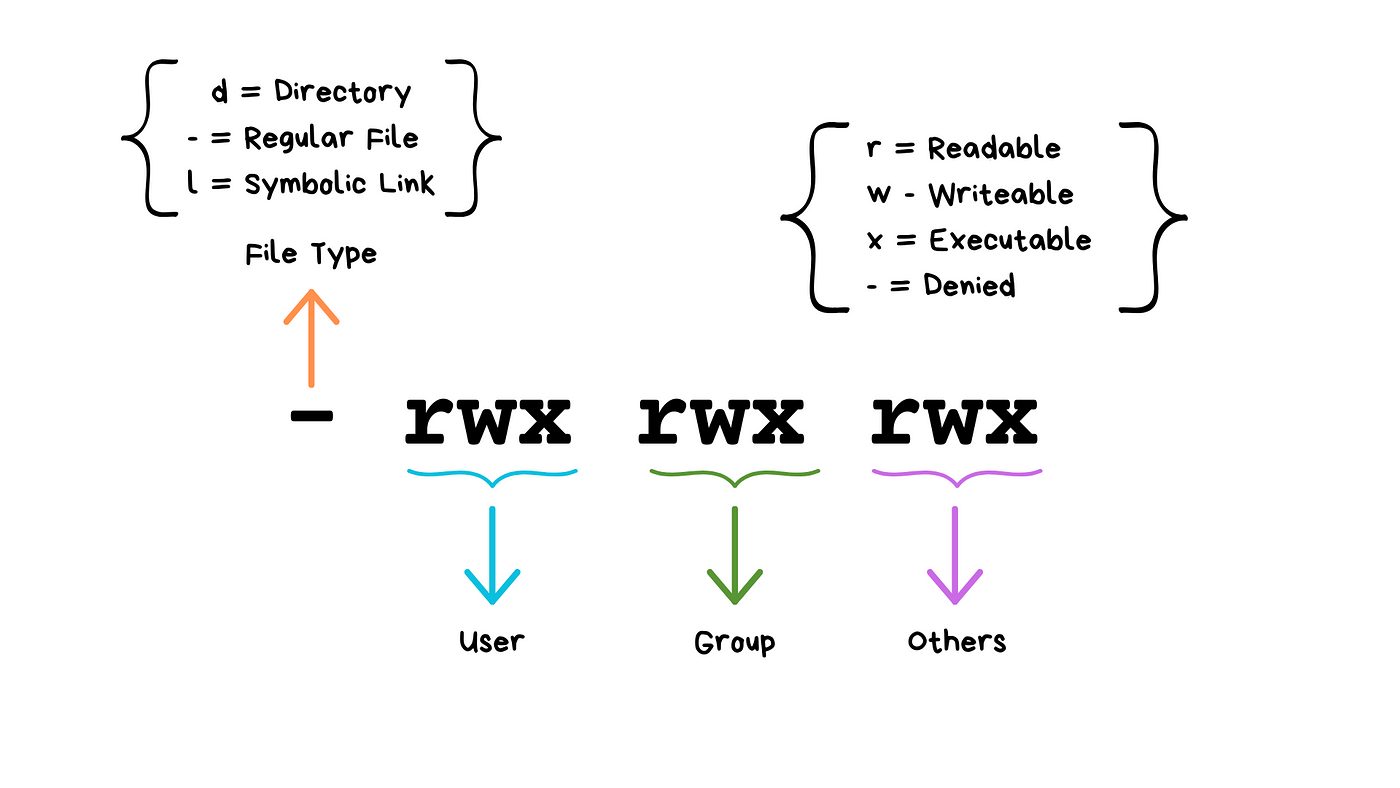

Understanding ls -la Output

-rw-r--r-- 1 user group 1024 Jan 15 10:30 filename.txt

drwxr-xr-x 2 user group 4096 Jan 15 10:25 dirname

(Don't worry about "groups"!)

We will see these kinds of permissions again in Rust programming!

Common Permission Patterns

rw-r--r--: Files you can edit, others can readrwxr-xr-x: Programs you can run, others can read/runrw-------: Private files only you can access

Don't have permission?

You can use sudo!

sudo rm <protected_file> # removes file even if you do not have permissions

Combining Commands with Pipes

ls | grep ".txt" # List only .txt files

cat file.txt | head -5 # Show first 5 lines of file

ls -l | wc -l # Count number of files in directory

# Find large files

ls -la | sort -k5 -nr | head -10

# Count total lines in all rust files

cat *.rs | wc -l

# Save output of command in a file called `results.txt`

ls -la > results.txt

ls -la >> results.txt # append

How does Shell find your commands and programs

cargo --version # uses our earlier installation of Rust

firefox # opens firefox!

When you execute a command, shell looks for an executable file with that exact name in specific locations (folders).

which cargo

which firefox

These specific locations are defined by the PATH environment variable.

echo $PATH

Question: Say we run a new command and get an error that says the shell cannot find it or recognize it. What could the reasons possibly be?

Shell scripts

Shell script files typically use the extension *.sh, e.g. script.sh.

Shell script files start with a shebang line, #!/bin/bash. They tell the computer which shell to use for that file!

#!/bin/bash

echo "Hello world!"

To execute shell script you can use the command:

source script.sh

In Class Activity

Part 1: Access/Install Terminal Shell

Directions for MacOS Users and Windows Users.

macOS Users:

Your Mac already has a terminal! Here's how to access it:

-

Open Terminal:

- Press

Cmd + Spaceto open Spotlight - Type "Terminal" and press Enter

- Or: Applications → Utilities → Terminal

- Press

-

Check Your Shell:

echo $SHELL # Modern Macs use zsh, older ones use bash -

Optional: Install Better Tools (do this after class):

Install Homebrew (package manager for macOS)

/bin/bash -c "$(curl -fsSL https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Homebrew/install/HEAD/install.sh)"Install useful tools

brew install tree # Visual directory structurebrew install ripgrep # Fast text search

Windows Users:

Windows has several terminal options. For this exercise we recommend Option 1, Git bash.

When you have more time, you might want to explore Windows Subsystem for Linux so you can have a full, compliant linux system accessible on Windows.

PowerShell aliases some commands to be Linux-like, but they are fairly quirky.

We recommend Git Bash or WSL:

-

Option A: Git Bash (Easier)

- Download Git for Windows from git-scm.com

- During installation, select "Use Git and optional Unix tools from the Command Prompt"

- Open "Git Bash" from Start menu

- This gives you Unix-like commands on Windows

-

Option B (do this after class): Windows Subsystem for Linux (or for shortWSL)

# Run PowerShell as Administrator, then: wsl --install # Restart your computer # Open "Ubuntu" from Start menu -

Option C (acceptable for today if you have to): PowerShell (Built-in)

- Press

Win + Xand select "PowerShell" - Note: depending on your version, some commands may differ from what we will show you (uses

dirinstead ofls, etc.) - Not recommended for this course (or life in general).

- Press

Verify Your Setup (Both Platforms)

Run each of these commands in your terminal of choice:

pwd # Should show your current directory

ls # Should list files (macOS/Linux) or use 'dir' (PowerShell)

which ls # Should show path to ls command (if available)

echo "Hello!" # Should print Hello!

Part 2: Mini Scavenger Hunt

Complete these steps using only the command line!.

You can work in groups of up to 3 people.

You can use echo "text" > file_name to write to the file, or text editor nano.

Feel free to reference the cheat sheet below, the notes above, or use Google for help!

- Navigate to your desktop directory/folder

Hint1: use

cd <path to desktop>to navigate.

Hint2: On mac, your desktop is located at

~/Desktop. On Windows, it is usually underc:\Users\<your username>\Desktop.

Hint3: verify you are in your desktop folder using

pwd.

- Create a directory called

treasure_huntin your course projects folder.

Hint: use

mkdir.

- In that directory create a file called

command_line_scavenger_hunt.txtthat contains your name and the name of your group members, if any.

Hint: confirm the content of your file using

cat <filename>.txt.

- Then, run these lines and record the output into that

.txtfile:

whoami # What's your username?

hostname # What's your computer's name?

pwd # Where do you start?

echo $HOME # What's your home directory path?

Hint: use

>>to append the output of a command to your file!

-

Inside the same directory, create another text file named

clue_1.txtwith the content "The treasure is hidden in plain sight" -

Create a subdirectory called

secret_chamber -

In the

secret_chamberdirectory, create a file calledclue_2.txtwith the content "Look for a hidden file" -

Create a hidden file in the

secret_chamberdirectory called.treasure_map.txtwith the content "Congratulations. You found the treasure" -

When you're done, change to the parent directory of

treasure_huntand run the commandzip -r treasure_hunt.zip treasure_hunt.- Or if you are on Git Bash, you may have to use the command

tar.exe -a -c -f treasure_hunt.zip treasure_hunt

- Or if you are on Git Bash, you may have to use the command

On windows, if you are unable to create this zip file, add an

error.txtfile insidetreasure_huntand put the error you received in it. You can then use the regular Windows graphical interface to zip the files.

-

Upload

treasure_hunt.zipto gradescope. You only need to upload once per group. -

Optional: For Bragging Rights Create a shell script that does all of the above commands and upload that to Gradescope as well.

Deadline: If you are not able to finish this exercise in class, you'll have until 11:55PM tonight to finish it from home and upload to Gradescope. If you need help, ask us questions via Piazza.

Command Line Cheat Sheet

Basic Navigation & Listing

Mac/Linux (Bash/Zsh) or Windows with Git Bash or Linux subsystem:

# Navigate directories

cd ~ # Go to home directory

cd /path/to/directory # Go to specific directory

pwd # Show current directory

# List files and directories

ls # List files

ls -la # List all files (including hidden) with details

ls -lh # List with human-readable file sizes

ls -t # List sorted by modification time

Windows (PowerShell/Command Prompt):

# Navigate directories

cd ~ # Go to home directory (PowerShell)

cd %USERPROFILE% # Go to home directory (Command Prompt)

cd C:\path\to\directory # Go to specific directory

pwd # Show current directory (PowerShell)

cd # Show current directory (Command Prompt)

# List files and directories

ls # List files (PowerShell)

dir # List files (Command Prompt)

dir /a # List all files including hidden

Get-ChildItem -Force # List all files including hidden (PowerShell)

Finding Files

Mac/Linux:

# Find files by name

find /home -name "*.pdf" # Find all PDF files in /home

find . -type f -name "*.log" # Find log files in current directory

find /usr -type l # Find symbolic links

# Find files by other criteria

find . -type f -size +1M # Find files larger than 1MB

find . -mtime -7 # Find files modified in last 7 days

find . -maxdepth 3 -type d # Find directories up to 3 levels deep

Windows:

# PowerShell - Find files by name

Get-ChildItem -Path C:\Users -Filter "*.pdf" -Recurse

Get-ChildItem -Path . -Filter "*.log" -Recurse

dir *.pdf /s # Command Prompt - recursive search

# Find files by other criteria

Get-ChildItem -Recurse | Where-Object {$_.Length -gt 1MB} # Files > 1MB

Get-ChildItem -Recurse | Where-Object {$_.LastWriteTime -gt (Get-Date).AddDays(-7)} # Last 7 days

Counting & Statistics

Mac/Linux:

# Count files

find . -name "*.pdf" | wc -l # Count PDF files

ls -1 | wc -l # Count items in current directory

# File and directory sizes

du -sh ~/Documents # Total size of Documents directory

du -h --max-depth=1 /usr | sort -rh # Size of subdirectories, largest first

ls -lah # List files with sizes

Windows:

# Count files (PowerShell)

(Get-ChildItem -Filter "*.pdf" -Recurse).Count

(Get-ChildItem).Count # Count items in current directory

# File and directory sizes

Get-ChildItem -Recurse | Measure-Object -Property Length -Sum # Total size

dir | sort length -desc # Sort by size (Command Prompt)

Text Processing & Search

Mac/Linux:

# Search within files

grep -r "error" /var/log # Search for "error" recursively

grep -c "hello" file.txt # Count occurrences of "hello"

grep -n "pattern" file.txt # Show line numbers with matches

# Count lines, words, characters

wc -l file.txt # Count lines

wc -w file.txt # Count words

cat file.txt | grep "the" | wc -l # Count lines containing "the"

Windows:

# Search within files (PowerShell)

Select-String -Path "C:\logs\*" -Pattern "error" -Recurse

(Select-String -Path "file.txt" -Pattern "hello").Count

Get-Content file.txt | Select-String -Pattern "the" | Measure-Object

# Command Prompt

findstr /s "error" C:\logs\* # Search for "error" recursively

find /c "the" file.txt # Count occurrences of "the"

System Information

Mac/Linux:

# System stats

df -h # Disk space usage

free -h # Memory usage (Linux)

system_profiler SPHardwareDataType # Hardware info (Mac)

uptime # System uptime

who # Currently logged in users

# Process information

ps aux # List all processes

ps aux | grep chrome # Find processes containing "chrome"

ps aux | wc -l # Count total processes

Windows:

# System stats (PowerShell)

Get-WmiObject -Class Win32_LogicalDisk | Select-Object Size,FreeSpace

Get-WmiObject -Class Win32_ComputerSystem | Select-Object TotalPhysicalMemory

(Get-Date) - (Get-CimInstance Win32_OperatingSystem).LastBootUpTime # Uptime

Get-LocalUser # User accounts

# Process information

Get-Process # List all processes

Get-Process | Where-Object {$_.Name -like "*chrome*"} # Find chrome processes

(Get-Process).Count # Count total processes

# Command Prompt alternatives

wmic logicaldisk get size,freespace # Disk space

tasklist # List processes

tasklist | find "chrome" # Find chrome processes

File Permissions & Properties

Mac/Linux:

# File permissions and details

ls -l filename # Detailed file information

stat filename # Comprehensive file statistics

file filename # Determine file type

# Find files by permissions

find . -type f -readable # Find readable files

find . -type f ! -executable # Find non-executable files

Windows:

# File details (PowerShell)

Get-ItemProperty filename # Detailed file information

Get-Acl filename # File permissions

dir filename # Basic file info (Command Prompt)

# File attributes

Get-ChildItem | Where-Object {$_.Attributes -match "ReadOnly"} # Read-only files

Network & Hardware

Mac/Linux:

# Network information

ip addr show # Show network interfaces (Linux)

ifconfig # Network interfaces (Mac/older Linux)

networksetup -listallhardwareports # Network interfaces (Mac)

cat /proc/cpuinfo # CPU information (Linux)

system_profiler SPHardwareDataType # Hardware info (Mac)

Windows:

# Network information (PowerShell)

Get-NetAdapter # Network interfaces

ipconfig # IP configuration (Command Prompt)

Get-WmiObject Win32_Processor # CPU information

Get-ComputerInfo # Comprehensive system info

Platform-Specific Tips

Mac/Linux Users:

- Your home directory is

~or$HOME - Hidden files start with a dot (.)

- Use

man commandfor detailed help - Try

which commandto find where a command is located

Windows Users:

- Your home directory is

%USERPROFILE%(Command Prompt) or$env:USERPROFILE(PowerShell) - Hidden files have the hidden attribute (use

dir /ahto see them) - Use

Get-Help commandin PowerShell orhelp commandin Command Prompt for detailed help - Try

where commandto find where a command is located

Universal Tips:

- Use Tab completion to avoid typing long paths

- Most shells support command history (up arrow or Ctrl+R)

- Combine commands with pipes (

|) to chain operations - Search online for "[command name] [your OS]" for specific examples

Rust Variables and Types

or how I learned to stop worrying and love the types1

Lecture 5: Monday, February 2, 2026, and

Lecture 6: Wednesday, February 4, 2026, and

Lecture 7: Friday, February 6, 2026.

Code examples

Rust is a statically typed programming language! Every variable must have its type known at compile time. This is a stark difference from Python, where a variable can take on different values from different types dynamically.

This has some really deep consequences that differentiate programming in Rust from that in Python.

To illustrate this better, let's start with a simple motivating example from Python.

Motivating example

Let's start with the following simple example from Python. Let's say we have two Python lists names and grades.

The first stores the names of different students in a class. The second one stores their grades. These lists are index-aligned:

the student whose name is at names[i] has grade grades[i].

names = ["Kinan", "Matt", "Taishan", "Zach", "Kesar", "Lingie", "Emir"]

grades = [ 0, 100, 95, 88, 99, 98, 97]

# Kinan's grade is 0, Kesar's grade is 99

Now, imagine we need to write some Python code to print the grade of a student given their name. Let's say the name

of this target student is stored in a variable called target.

# Alternatively, the value of target might be provided by the

# user, e.g., via some nice UI

target = "Kesar"

Our first observation is that the grades and names are index-aligned. So to find the grade of "Kesar",

we need to find the index of "Kesar" in names. Let's do that using a helper function. Here's a reasonable first attempt:

def find_index(target, names):

# iterate from 0 up to the length of names.

for i in range(len(names)):

if target == names[i]:

return i

Now, we can use find_index to retrieve the grade of "Kesar" as follows.

target = "Kesar"

index = find_index(target, names)

print(grades[index])

This indeed works! and if we run it, we will see the correct output.

99

The code will also work for many other values of target, e.g. "Kinan", "Matt", "Emir", etc.

However, what about if we search for a target who is not in names? For example target = tom?

In this case, find_index never finds a name equal to target, and so its for loop finishes without ever returning any i.

def find_index(target, names):

for i in range(len(names)):

# when target = 'Tom'

# then this condition is False for all elements in names

if target == names[i]:

# this is never reached for target = 'Tom'

return i

# instead, when target='Tom' the execution reachs this point.

# What should we return here?

return ?????

A good follow up question is what should find_index return in such a case?

Discuss this with your neighbor and come up with a candidate value!

Option 1: return -1

Many languages, e.g., Java, use -1 to indicate having not found something. Let's consider what happens

if we try that out in our Python example. In this case, our find_index function becomes:

def find_index(target, names):

for i in range(len(names)):

if target == names[i]:

return i

return -1

So what would happen in this case if we search for a target that does not exist?

target = "Tom"

index = find_index(target, names)

print(grades[index])

In this case, find_index returns -1. So, index is equal to -1, and we print grades[-1]. In python, an index of -1

corresponds to the last element in the list. So, our program will print the last grade in the list.

97

This is no good! Tom's grade is not 97! That's Emir's grade. In fact, Tom has no grade at all!!! This kind of silent problem is the worst kind you can have, because you may not even realize that it is a problem. Imagine if there were thousands of students. You run the code and see this output. You may not realize that the target you were looking for isn't there (or that you made a typo the student's name), and think that the output is accurate!

You can find the code for this option here.

Option 2: return "Not found"

A different option would be to return "Not found" or some special kind of similar message.

This is curious! find_index now sometimes returns an index (which is a number, i.e., of type int), and sometimes returns a string (in Python, that type is called str)!

def find_index(target, names):

for i in range(len(names)):

if target == names[i]:

return i

return "Not found"

target = "Tom"

index = find_index(target, names)

print(grades[index])

In this case, index is equal to `"Not found". So, our last line is equivalent to saying:

grades["Not found"]

This makes no sense! Imagine someone asks you to look up an element in a list at position "Not found", or position "hello!", or any other string. What would you do? I would freak out. So does Python, running this code results in the following error:

TypeError: list indices must be integers or slices, not str

In my opinion, this is a little better than option 1. At least, it is visible and obvious that something wrong went on. But it is still not good.

You can find the code for this option here.

Option 3: return "Not found" then manually check the type

How about we check the type of whatever find_index returns before we attempt to access the list of grades?

It turns out we can ask Python to tell us what type a variable (or any value or expression) has! This happens at runtime: we cannot actually determine the type ahead of time. Only when the program is executing/all inputs have been supplied.

def find_index(target, names):

for i in range(len(names)):

if target == names[i]:

return i

return "Not found"

target = "Tom"

index = find_index(target, names)

if type(index) == int:

print(grades[index])

else:

print('not found')

If we run this code, the output we see is:

not found

Finally, we have a solution that works! If the name is in the list, the program will print the grade, and otherwise

it will print not found.

One of the reasons we had to go through all these steps is that Python has dynamic typing. The same function or variable may return or contain different types when you run the program with different inputs.

Furthermore, neither Python nor our program help us out by telling us what the possible types are, or that we checked all of them. We have to figure this out ourselves, and remember to do the checking manually.

You can find the code for this option here.

What about Rust?

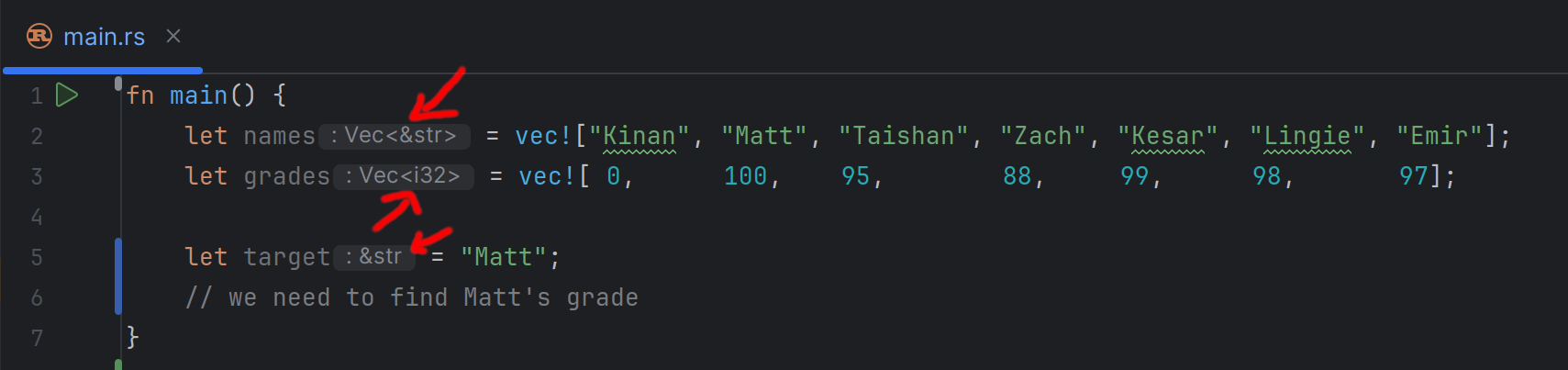

Let's look at the same problem in Rust. The beginning is similar to the Python code.

fn main() { let names = vec!["Kinan", "Matt", "Taishan", "Zach", "Kesar", "Lingie", "Emir"]; let grades = vec![ 0, 100, 95, 88, 99, 98, 97]; let target = "Matt"; // we need to find Matt's grade }

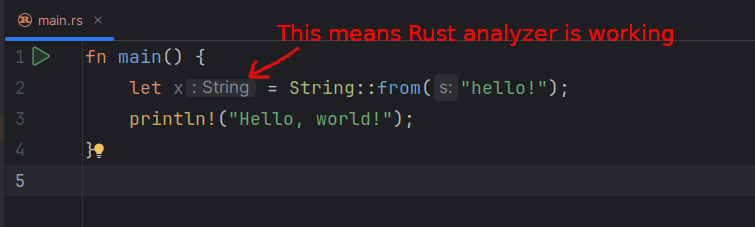

However, we can already see one difference. If you look at this code in a Rust IDE, such as VSCode, you will notice that it automatically fills in the type of each variable. As shown in the screenshot below.

For example, VScode tells us that the type of target is a string (Rust calls this &str, more on the & part later), and the type of grades is Vec<i32>, in other words, a vector (which is what Rust calls

Python lists) that contains i32s in it!

This is quite cool. Not only do we know the type of every variable. We also know information about any other elements or values inside that variable. E.g., the type of the elements inside a vector!

It turns out, we can also write these types out explicitly ourselves in the program. For example:

fn main() { let names: Vec<&str> = vec!["Kinan", "Matt", "Taishan", "Zach", "Kesar", "Lingie", "Emir"]; let grades: Vec<i32> = vec![ 0, 100, 95, 88, 99, 98, 97]; let target = "Matt"; // we need to find Matt's grade }

Furthermore, if we specify types that are inconsistent with the values assigned to a variable, we will get a compiler error!

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // This should not work: "Kinan" is a string, not an i32. let target: i32 = "Kinan"; }

error[E0308]: mismatched types

|

| let target: i32 = "Kinan";

| --- ^^^^^^^ expected `i32`, found `&str`

This is a consequence of an important design decision in Rust. It follows a strong static typing philosophy, where every variable (and expression) needs to have a single type that is known statically. In otherwords, a type that is determined at compile time before the program runs and does not change if you run the program with different inputs again.

Fortunately, Rust has support for type inference. With type inference, we do not have to write out every type in the program explicitly. Instead, we can often (but not always!) skip the types, and let the language deduce it automatically. Hence, VSCode being able to show us the types in the example above.

Now, let's move on to the next step in the program. We need to implement a find_index function in Rust.

In Rust, function definitions (or more accurately, function signatures) look like this:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn find_index(target: &str, names: Vec<&str>) -> usize { // the body of the function with all its code goes here. } }

There are a few important differences between this and Python:

- Rust uses

fn(short for function) to indicate a function definition, Python usesdef(short for definition). - Every argument to the function must have an explicilty defined type in Rust. For example, we explicitly state that

targethas type&str(i.e. string). - The function must state explicitly what type of values it returns (if any). This is the

-> usizepart, which tells us that this function return values of typeusize(Ausizein Rust is a type that describes non-negative numbers that can be used as indices or addresses on the computer).

Now, we can try to fill in the function body, mimicing the same logic from Python but using Rust syntax.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn find_index(target: &str, names: Vec<&str>) -> usize { for i in 0..names.len() { if target == names[i] { return i; } } return "Not Found"; } }

We can see a few syntax differences that we already covered earlier in class:

- Python relies on

:and indentation to specify where a code block starts and end (e.g., the body of a function, for loop, or if statement). Rust instead uses{and}. - Rust's syntax for ranges is