Overview

This course builds on DS110 (Python for Data Science) by expanding on programming language, systems, and algorithmic concepts introduced in the prior course. The course begins by introducing shell commands, using command windows and git version control. These are practical skills that are essential a practicing data scientist.

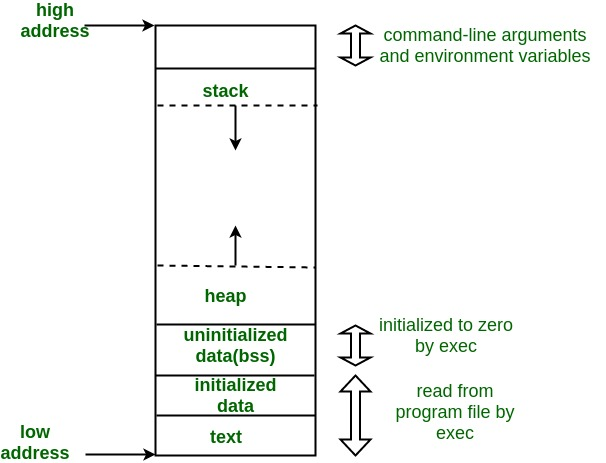

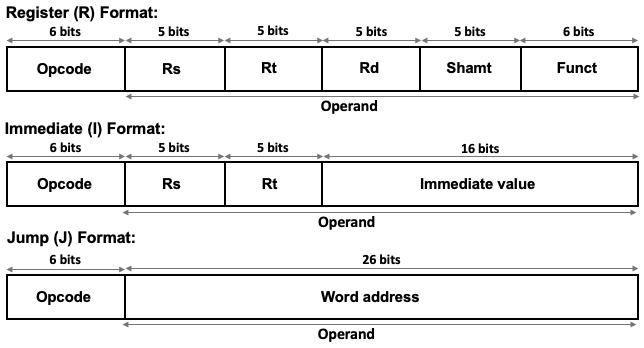

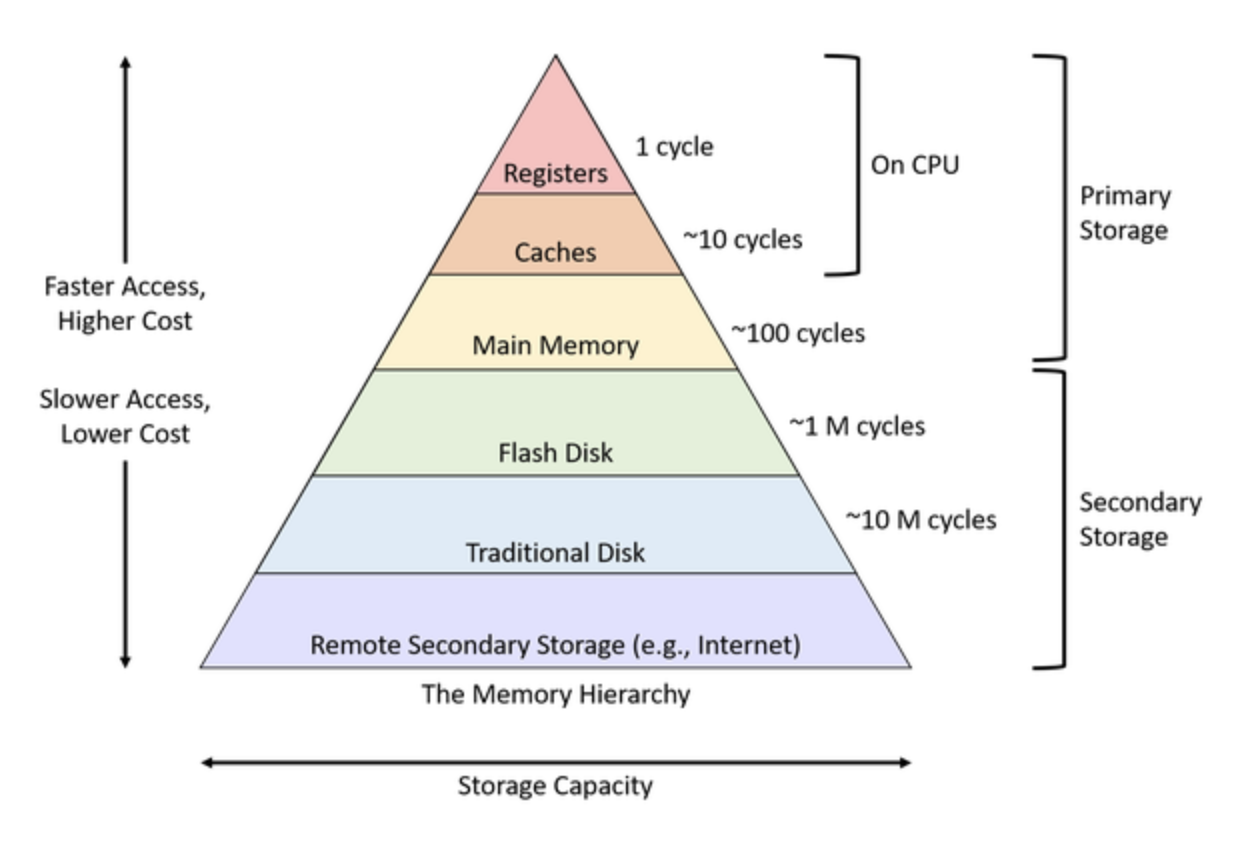

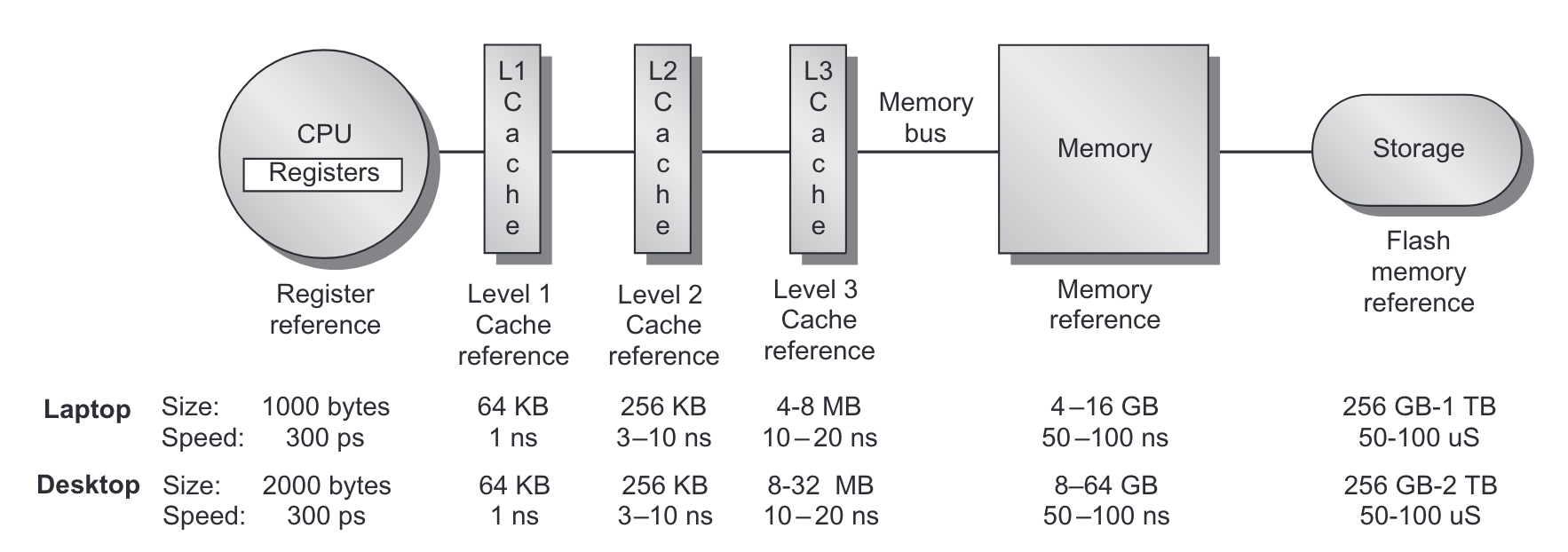

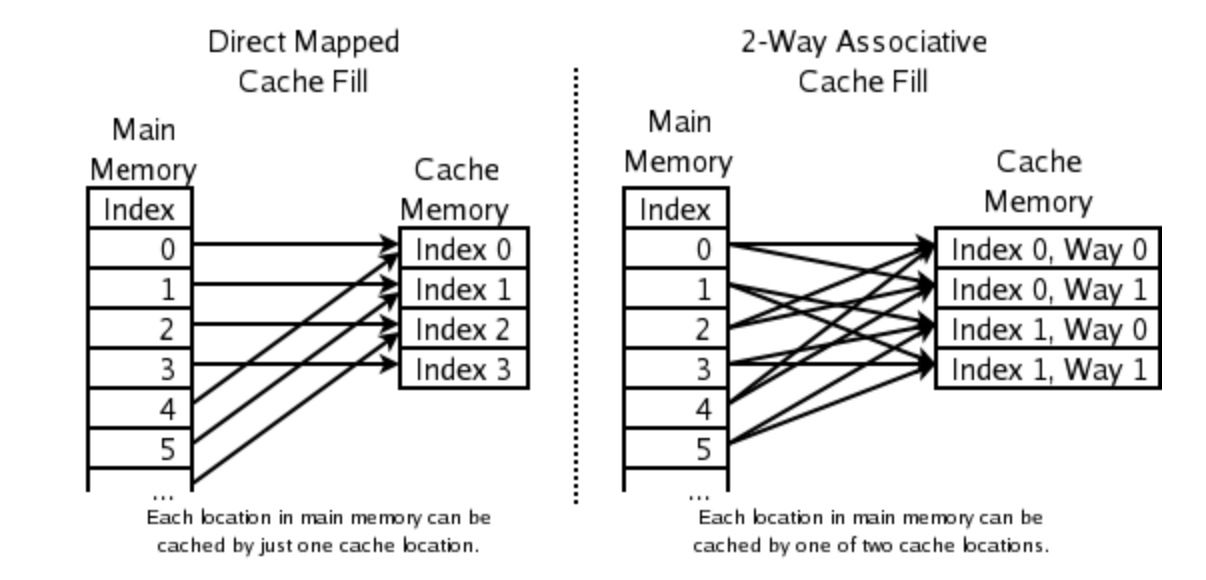

You will then explore the different types of programming languages and be introduced to important systems level concepts such as computer architecture, compilers and file systems. It is vital to conceptualize how programs work at the machine level.

The bulk of the course is spent learning Rust, a modern, high-performance and more secure programming language. Rust is a systems programming language that is designed to be safe, fast, and memory efficient. It is a great language to learn because it is a low-level language that is still easy to read and write. More and more performant data science libraries and tools are written in Rust for these reasons.

You will be expected to read relevant parts of the Rust Language Book before each lecture, where we will then present the material in more depth. You will then have the opportunity to practice what you just learned with in-class activities. There will be approximately seven homeworks, two midterms, and a final exam.

Learning any new programming language is significant time and effort investment and it is vital to continually practice what you learn throughout the entire semester.

Prerequisites: CDS 110 or equivalent

B1 Course Staff

Section B1 Instructor: Thomas Gardos

Email: tgardos@bu.edu

Office hours: 2-3pm Tuesdays and Thursdays @ CCDS 1623, and by appointment.

If you want to meet but cannot make office hours, send a private note on Piazza with at least 2 suggestions for times that you are available, and we will find a time to meet.

B1 TAs

See Piazza resource page for office hours and contact information.

- Gabriel Maayan

- Zachary Gentile

B1 CAs

See Piazza resource page for office hours and contact information.

- Emir Tali

- Matthew Morris

- Kesar Narayan

- Lingjie Su

Lectures and Discussions

B1 Lecture: Tuesdays, Thursdays 11:00am-12:15pm (SHA 110)

Section B Discussions (Fridays, 50 min):

- B2: Fri 12:20pm – 1:10pm, IEC B10 (888 Commonwealth Ave.)

- B3: Tue 1:25pm – 2:15pm, CGS 313 (871 Commonwealth Ave.)

- B4: Tue 2:30pm – 3:20pm, CDS 164 (665 Commonwealth Ave.)

- B5: Tue 3:35pm – 4:25pm, CDS 164 (665 Commonwealth Ave.)

Note: There are two sections of this course, they cover similar material

but the discussion sections and grading portals are different. These are not interchangeable, you must attend the lecture and discussion sessions for your section!

Course Websites

Links shared via email.

-

Piazza

- Lecture Recordings

- Announcements and additional information

- Questions and discussions

-

Course Notes:

- Syllabus (this document)

- Interactive lecture notes

-

Gradescope

- Homework, project, project proposal submissions

- Gradebook

-

GitHub Classroom: URL TBD

Course Content Overview

For a complete list of modules and topics that will be kept up-to-date as we go through the term, see B1 Lecture Schedule (TTH).

Course Format

Lectures will involve extensive hands-on practice. Each class includes:

- Interactive presentations of new concepts

- Small-group exercises and problem-solving activities

- Discussion and Q&A

Because of this active format, regular attendance and participation is important and counts for a significant portion of your grade (15%).

Discussions will review lecture material, provide homework support, and will adapt over the semester to the needs of the class. We will not take attendance but our TAs make this a great resource!

Pre-work will be assigned before most lectures to prepare you for in-class activities. These typically include readings plus a short ungraded quiz. We will also periodically ask for feedback and reflections on the course between lectures.

Homeworks will be assigned roughly weekly at first, and there will be longer two-week assignments later, reflecting the growing complexity of the material.

Exams Two midterms and a cumulative final exam covering theory and short hand-coding problems (which we will practice in class!)

The course emphasizes learning through practice, with opportunities for corrections and growth after receiving feedback on assignments and exams.

Course Policies

Grading Calculations

Your grade will be determined as:

- 15% homeworks (~9 assignments)

- 20% midterm 1

- 20% midterm 2

- 25% final exam

- 15% in-class activities and attendance polls

- 5% pre-work and surveys

We will use the standard map from numeric grades to letter grades

(>=93 is A, >=90 is A-, etc).

For the midterm and final, we may add a fixed number of "free" points to

everyone uniformly to effectively curve the exam at our discretion - this will

never result in a lower grade for anyone.

We will use gradescope to track grades over the course of the semester, which you can verify at any time and use to compute your current grade in the course for yourself.

Homeworks

Homework assignments will be submitted by uploading them to GitHub Classroom. We will use Rust tests and GitHub Actions to automatically test your code. We'll also inspect for evidence of good git version control practices. You will get more instructions on homeworks in class and on Piazza.

You are expected to complete homeworks yourself and not have AI do it for you. Per the AI policy below, you are allowed to use AI to help you understand concepts, debug your code, or generate ideas. You should understand that this may may help or impede your learning depending on how you use it.

If you use AI for an assignment, you must cite what you used and how you used it (for brainstorming, autocomplete, generating comments, fixing specific bugs, etc.). You must understand the solution well enough to explain it during a small group or discussion in class. You should be able to explain your code to a peer in a way that is easy to understand.

Your professor and TAs/CAs are happy to help you write and debug your own code during office hours, but we will not help you understand or debug code that is generated by AI.

For more information see the CDS policy on GenAI.

Exams

The final will be during exam week, date and location TBD. The two midterms will be in class during normal lecture time.

If you have a valid conflict with a test date, you must tell me as soon as you are aware, and with a minimum of one week notice (unless there are extenuating circumstances) so we can arrange a make-up test.

If you need accommodations for exams, schedule them with the Testing Center as soon as exam dates are firm. See below for more about accommodations.

Deadlines and late work

Homeworks will be due on the date specified in gradescope and github classroom.

If your work is up to 48-hours late, you can still qualify for up to 80% credit for the assignment. After 48 hours, late work will not be accepted unless you have made prior arrangements due to extraordinary circumstances.

Because of our autograding system, it is possible to get partial credit for homework submitted on time, and then 80% credit for remaining work submitted up to 48 hours late.

Collaboration

You are free to discuss problems and approaches with other students but must do your own writeup. If a significant portion of your solution is derived from someone else's work (your classmate, a website, a book, etc), you must cite that source in your writeup. You will not be penalized for using outside sources as long as you cite them appropriately.

You must also understand your solution well enough to be able to explain it if asked.

Academic honesty

You must adhere to BU's Academic Conduct Code at all times. Please be sure to read it here. In particular: cheating on an exam, passing off another student's work as your own, or plagiarism of writing or code are grounds for a grade reduction in the course and referral to BU's Academic Conduct Committee. If you have any questions about the policy, please send me a private Piazza note immediately, before taking an action that might be a violation.

AI use policy

You are allowed to use GenAI (e.g., ChatGPT, GitHub Copilot, etc) to help you understand concepts, debug your code, or generate ideas. You should understand that this may may help or impede your learning depending on how you use it.

If you use GenAI for an assignment, you must cite what you used and how you used it (for brainstorming, autocomplete, generating comments, fixing specific bugs, etc.). You must understand the solution well enough to explain it during a small group or discussion in class.

Your professor and TAs/CAs are happy to help you write and debug your own code during office hours, but we will not help you understand or debug code that generated by AI.

For more information see the CDS policy on GenAI.

Attendance and participation

Since a large component of your learning will come from in-class activities and discussions, attendance and participation are essential and account for 15% of your grade.

Attendance will be taken in lecture through Piazza polls which will open at various points during the lecture. Understanding that illness and conflicts arise, up to 4 absences are considered excused and will not affect your attendance grade.

In most lectures, there will be time for small-group exercises. To receive participation credit on these occasions, you must submit a group assignment on Gradescope. These submissions will not be graded for accuracy, just for good-faith effort.

Occasionally, I may ask for volunteers, or I may call randomly upon students or groups to answer questions or present problems during class.

Absences

This course follows BU's policy on religious observance. Otherwise, it is generally expected that students attend lectures and discussion sections. If you cannot attend classes for a while, please let me know as soon as possible. If you miss a lecture, please review the lecture notes and lecture recording. If I cannot teach in person, I will send a Piazza announcement with instructions.

Accommodations

If you need accommodations, let me know as soon as possible. You have the right to have your needs met, and the sooner you let me know, the sooner I can make arrangements to support you.

This course follows all BU policies regarding accommodations for students with documented disabilities. If you are a student with a disability or believe you might have a disability that requires accommodations, please contact the Office for Disability Services (ODS) at (617) 353-3658 or access@bu.edu to coordinate accommodation requests.

If you require accommodations for exams, please schedule that at the BU testing center as soon as the exam date is set.

Re-grading

You have the right to request a re-grade of any homework or test. All regrade requests must be submitted using the Gradescope interface. If you request a re-grade for a portion of an assignment, then we may review the entire assignment, not just the part in question. This may potentially result in a lower grade.

Corrections

You are welcome to submit corrections on midterms. This is an opportunity to take the feedback you have received, reflect on it, and then demonstrate growth.

We will provide solutions as part of the midterm grading process, so simply resubmitting the solution will earn you no credit.

Instead, what we are looking for is a personal reflection written in your own words that addresses the following:

- A clear explanation of the mistake

- What misconception(s) led to it

- An explanation of the correction

- What you now understand that you didn't before

After receiving grades back, you will have one week to submit corrections. You can only submit corrections on a good faith attempt at the initial submission (not to make up for a missed assignment).

Satisfying this criteria completely for any particular problem will earn you back 50% of the points you originally lost (no partial credit).

The Rust Language Book

The primary reference will be the Rust Language Book and these course notes.

T-TH B1 Lecture Schedule

Note: Schedule may updated. Check back regularly.

Note: Homeworks will be distributed via Gradescope and GitHub Classroom. We'll also post notices on Piazza.

Lecture Schedule

| Date | Lecture | Readings/Homework |

|---|---|---|

| Week 1 | --- | --- |

| Jan 20 | Lecture 1: Course Overview, Why Rust | |

| Jan 22 | Lecture 2: Hello Shell | |

| Week 2 | --- | --- |

| Jan 27 | Lecture 3: Hello Git | |

| Jan 29 | Lecture 4: Hello Rust | |

| Week 3 | --- | --- |

| Feb 3 | Lecture 5: Programming Languages, Guessing Game Part 1 | |

| Feb 5 | Lecture 6: Complete Guessing Game Part 1 and start Vars and Types | |

| Week 4 | --- | --- |

| Feb 10 | Lecture 7: Vars and Types, | |

| Feb 12 | Lecture 8: Finish Vars and Types, Cond Expressions, Functions, | |

| Week 5 | --- | --- |

| Feb 17 | No Class -- Monday Schedule | |

| Feb 19 | Lecture 9: Finish Functions, Loops Arrays, Tuples | |

| Week 6 | --- | --- |

| Feb 24 | Lecture 10: Enum and Match | |

| Feb 26 | Lecture 12: Start on Ownership and Borrowing, Strings and Vecs | |

| Week 7 | --- | --- |

| Mar 3 | Lecture 11: A1 Midterm 1 Review | |

| Mar 5 | 🧐📚 Midterm 1 📚🧐 | |

| 🏖️🏄🌴 | Spring Break | 🏖️🏄🌴 |

| Mar 7-15 | No Classes | |

| Week 8 | --- | --- |

| Mar 17 | Lecture 13: Structs, Method Syntax, Methods Revisited | |

| Mar 19 | Lecture 14: Slices, Modules, | |

| Week 9 | --- | --- |

| Mar 24 | Lecture 15: Crates, Rust Projects,Tests, Generics | |

| Mar 26 | Lecture 16: Generics, Traits | |

| Week 10 | --- | --- |

| Mar 31 | Lecture 17: Lifetimes, Closures | |

| Apr 2 | Lecture 18: , Iterators, Iters Closures | |

| Week 11 | --- | --- |

| Apr 7 | Lecture 19 -- Midterm 2 Review | |

| Apr 9 | 🧐📚 Midterm 2 📚🧐 | |

| Week 12 | --- | --- |

| Apr 14 | Lecture 20: Complexity Analysis, Hash Maps (only) | |

| Apr 16 | Lecture 21: Hashing Functions, Hash Sets, linked lists, | |

| Week 13 | --- | --- |

| Apr 21 | Lecture 22: Stacks, Queues | |

| Apr 23 | Lecture 23: Collections Deep Dive, | |

| Week 14 | --- | --- |

| Apr 28 | Lecture 24: Algorithms and Data Science | |

| Apr 30 | Final Review -- 🎉 Last Day of Classes 🎉 | |

| Week 15 | --- | --- |

| May 5 (Tuesday) | 🧐📚 Final Exam 📚🧐 12:00 pm - 2:00 pm SHA 110 |

Knowledge Checks

This page is a continuous work in progress. Check back regularly for updates.

The intent of this page is to give you progressively more difficult challenges that you should master as the course progresses. You should attempt these with no notes, references or AI assistance, as you won't have those on the quizzes.

Don't move to the next challenge in each section until you have mastered the previous one.

If a section is marked with a prerequisite section, completed that first!

Knowledge checks up to ~ Jan. 29 lecture

Shell Commands

Prerequisite: None

In zsh or bash shell...

How do check what directory you are in?

How do you switch into a different directory?

How do you list contents of a directory?

How do you list detailed contents of a directory, including file permissions?

What do the first 10 letters represent in the detailed file listings?

What does tgardos and staff represent in the detailed file listings?

drwxr-xr-x@ 33 tgardos staff 1056 Feb 3 09:49 book

-rw-r--r--@ 1 tgardos staff 1438 Jan 21 14:59 book.toml

How do you list hidden files and directories in a directory?

What naming convention renders a file hidden?

What do the special characters . and .. represent in file paths?

How do you recall previous commands at the command line?

Hint: You can see previous commands with one keypress.

How do you list the most recently used commands?

Hint: This will print out a list of the most recent commands you issued.

Git Commands

Prerequisite: Shell Commands

How do you clone a repository?

After you clone a repo, are you in the local repo or do you have to switch to it?

How do you list the branches in a repository?

How do you switch to a different branch?

How do you create a new branch?

How do you check if you have changes or new files in your repository?

How do you stage changes in your repository?

Hint: You are adding them to the staging area.

How do you commit changes to your repository along with a commit message in one step?

How do you merge a branch into the main branch?

How do you push changes to a remote repository?

How do you pull changes from a remote repository?

Rust Command Line Tools

Prerequisite: Shell Commands

How do you create a new Rust project?

How do you build a Rust project?

How do you run a Rust program?

Basic Rust Syntax

From memory, write a main function in Rust that prints "Hey world! I got this!".

// Your code here

Ownership in Rust

Prerequisite: Complete Basic Rust Syntax

DS210 Course Overview

About This Module

This module introduces DS-210: Programming for Data Science, covering course logistics, academic policies, grading structure, and foundational concepts needed for the course.

Overview

This course builds on DS110 (Python for Data Science). That, or an equivalent is a prerequisite.

We will cover

- shell commands

- git version control

- programming languages

- computing systems concepts

And then spend the bulk of the course learning Rust, a modern, high-performance and more secure programming language.

Time permitting we dive into some common data structures and data science related libraries.

New Last Semester

We've made some significant changes to the course based on observations and course evaluations.

Question: What have you heard about the course? Is it easy? Hard?

Changes include:

- Moving course notes from Jupyter notebooks to Rust

mdbook- This is the same format used by the Rust language book

- Addition of in-class group activites for almost every lecture where you

can reinforce what you learned and practice for exams

- Less lecture content, slowing down the pace

- Homeworks that progressively build on the lecture material and better match exam questions (e.g. 10-15 line code solutions)

- Elimination of course final project and bigger emphasis on in-class activities and participation.

Teaching Staff and Contact Information

See B1 Course Staff.

Course Logistics

Course Websites

See welcome email for Piazza and Gradescope URLs.

-

Piazza:

- Lecture Notes

- Announcements and additional information

- Questions and discussions

-

Gradescope:

- Homework

- Gradebook

-

GitHub Classroom: URL TBD

Course objectives

This course teaches systems programming and data structures through Rust, emphasizing safety, speed, and concurrency. By the end, you will:

- Master key data structures and algorithms for CS and data science

- Understand memory management, ownership, and performance optimization

- Apply computational thinking to real problems

- Develop Rust skills that transfer to other languages

Why are we learning Rust?

- Learning a second programming language builds CS fundamentals and teaches you to acquire new languages throughout your career

- Systems programming knowledge helps you understand software-hardware interaction and write efficient, low-level code

We're using Rust specifically because:

- Memory safety without garbage collection lets you see how data structures work in memory (without C/C++ headaches)

- Strong type system catches errors at compile time, helping you write correct code upfront

- Growing adoption in data science and scientific computing across major companies and agencies

More shortly.

Course Timeline and Milestones

- Part 1: Foundations (command line, git) & Rust Basics (Weeks 1-3)

- Part 2: Core Rust Concepts & Data Structures (Weeks 4-5)

- Midterm 1 (~Week 5)

- Part 3: Advanced Rust & Algorithms (Weeks 6-10)

- Midterm 2 (~Week 10)

- Part 4: Data Structures and Algorithms (~Weeks 11-12)

- Part 5: Data Science & Rust in Practice (~Weeks 13-14)

- Final exam during exam week

Course Format

Lectures will involve hands-on practice. Each class includes:

- Interactive presentations of new concepts

- Small-group exercises and problem-solving activities

Because of this active format, regular attendance and participation is important and counts for a significant portion of your grade (15%).

Discussions will review and reinforce lecture material through and provide further opportunities for hands-on practice.

Pre-work will be assigned before most lectures to prepare you for in-class activities. These typically include readings plus a short ungraded quiz. The quizz questions will reappear in the lecture for participation credit.

Homeworks will be assigned roughly weekly before the midterm, and then longer two-week assigments after the deadline, reflecting the growing complexity of the material.

Exams 2 midterms and a cumulative final exam covering theory and short hand-coding problems (which we will practice in class!)

The course emphasizes learning through practice, with opportunities for corrections and growth after receiving feedback on assignments and exams.

More course policies

Let's switch to the syllabus to cover:

- grading calculations

- homeworks

- deadlines and late work

- collaboration

- academic honesty

- AI use policy discussed after class activity

- attendance and participation

- regrading

- corrections

In-class Activity

AI use discussion (20 min)

Think-pair-share style, each ~6-7 minutes, with wrap-up.

See Gradescope assignment. Forms teams of 3.

Round 1: Learning Impact

"How might GenAI tools help your learning in this course? How might they get in the way?"

Round 2: Values & Fairness

"What expectations do you have for how other students in this course will or won't use GenAI? What expectations do you have for the teaching team so we can assess your learning fairly given easy access to these tools?"

Round 3: Real Decisions

"Picture yourself stuck on a challenging Rust problem at 11pm with the midnight deadline looming. What options do you have? What would help you make decisions you'd feel good about? What would you do differently for the next homework?"

AI use policy

You are allowed to use GenAI (e.g., ChatGPT, GitHub Copilot, etc) to help you understand concepts, debug your code, or generate ideas.

You should understand that this may may help or impede your learning depending on how you use it.

If you use GenAI for an assignment, you must cite what you used and how you used it (for brainstorming, autocomplete, generating comments, fixing specific bugs, etc.).

You must understand the solution well enough to explain it during a small group or discussion in class.

Your professor and TAs/CAs are happy to help you write and debug your own code during office hours, but we will not help you understand or debug code that is generated by AI.

For more information see the CDS policy on GenAI.

How to Do Well in the Course

- All the usual advice about attending lectures and discussions, engaging, etc..

Insiders tips on how to do well in this particular course:

- Do the pre-work/pre-reading before lecture so you are seeing the concepts for a second time in the lecture.

- Actively engage in the pre-reading... try executing the code and making changes

- Do as much Rust coding as you can.. preferably 15-30 minutes per day

- Learning a programming language is like learning a human language, or learning and instrument or training for a sport... you need to practice regularly to get good at it.

- Exams are paper and pencil, so you need to write code quickly from memory.

- Use in-class activities and homework to practice for the exams... try to do as much of it as possible without autocomplete and AI assistance.

Intro surveys

Please fill out the intro survey posted on Gradescope.

Why Rust?

Why Systems Programming Languages Matter

Importance of Systems Languages:

- Essential for building operating systems, databases, and infrastructure

- Provide fine-grained control over system resources

- Enable optimization for performance-critical applications

- Foundation for higher-level languages and frameworks

Performance Advantages:

- Generally compiled languages like Rust are needed to scale to large, efficient deployments

- Can be 10x to 100x faster than equivalent Python code

- Better memory management and resource utilization

- Reduced runtime overhead compared to interpreted languages

Data Science and ML Libraries Written in Rust

- Polars - data processing and analysis library

- tiktoken - tokenization library for OpenAI models

- uv - package manager for Python

- Burn - A PyTorch like alterntive in Rust

- Candle - A minimalist ML framework for Rust

- ...

Memory Safety: A Critical Advantage

What is Memory Safety?

Memory safety prevents common programming errors that can lead to security vulnerabilities:

- Buffer overflows

- Use-after-free errors

- Memory leaks

- Null pointer dereferences

Industry Recognition:

Major technology companies and government agencies are actively moving to memory-safe languages:

- Google, Microsoft, Meta have efforts underway to move infrastructure code from C/C++ to Rust

- ...

White House Press Release

DARPA TRACTOR Program

CISA Recommendation

CISA -- The case for memory safe roadmaps

CISA -- Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency

CISA -- The case for memory safe roadmaps

CISA -- Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency

Programming Paradigms: Interpreted vs. Compiled

Interpreted Languages (e.g., Python):

Advantages:

- Interactive development environment

- Quick iteration and testing

- Rich ecosystem for data science (Jupyter, numpy, pandas)

- Easy to learn and prototype with

Compiled Languages (e.g., Rust):

Advantages:

- Superior performance and efficiency

- Early error detection at compile time

- Optimized machine code generation

- Better for production systems

Development Process:

- Write a program

- Compile it (catch errors early)

- Run and debug optimized code

- Deploy efficient executables

Technical Coding Interviews

And finally...

If you are considering technical coding interviews, they sometimes ask you to solve problems in a language other than python.

Many of the in-class activities and early homework questions will be Leetcode/HackerRank style challenges.

This is good practice!

Hello Shell!

About This Module

This module introduces you to the command-line interface and essential shell commands that form the foundation of systems programming and software development. You'll learn to navigate the file system, manipulate files, and use the terminal effectively for Rust development.

Prework & Reading

- Review this module.

- Review In Class Activity Part 1: Access/Install Terminal Shell and follow instructions to install and use the terminal shell.

Pre-lecture Reflections

Before class, consider these questions:

- What advantages might a command-line interface offer over graphical interfaces? What types of tasks seem well-suited for command-line automation?

- How does the terminal relate to the development workflow you've seen in other programming courses?

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, you should be able to:

- Create, copy, move, and delete files and directories at the command line

- Understand file permissions and ownership concepts

- Use pipes and redirection for basic text processing

- Set up an organized directory structure for programming projects

- Feel comfortable working in the terminal environment

Why the Command Line Matters

For Programming and Data Science:

# Quick file operations

ls *.rs # Find all Rust files

grep "TODO" src/*.rs # Search for TODO comments across files

wc -l data/*.csv # Count lines in all CSV files

Advantages over GUI:

- Speed: Much faster for repetitive tasks

- Precision: Exact control over file operations

- Automation: Commands can be scripted and repeated

- Remote work: Essential for server management

- Development workflow: Many programming tools use command-line interfaces

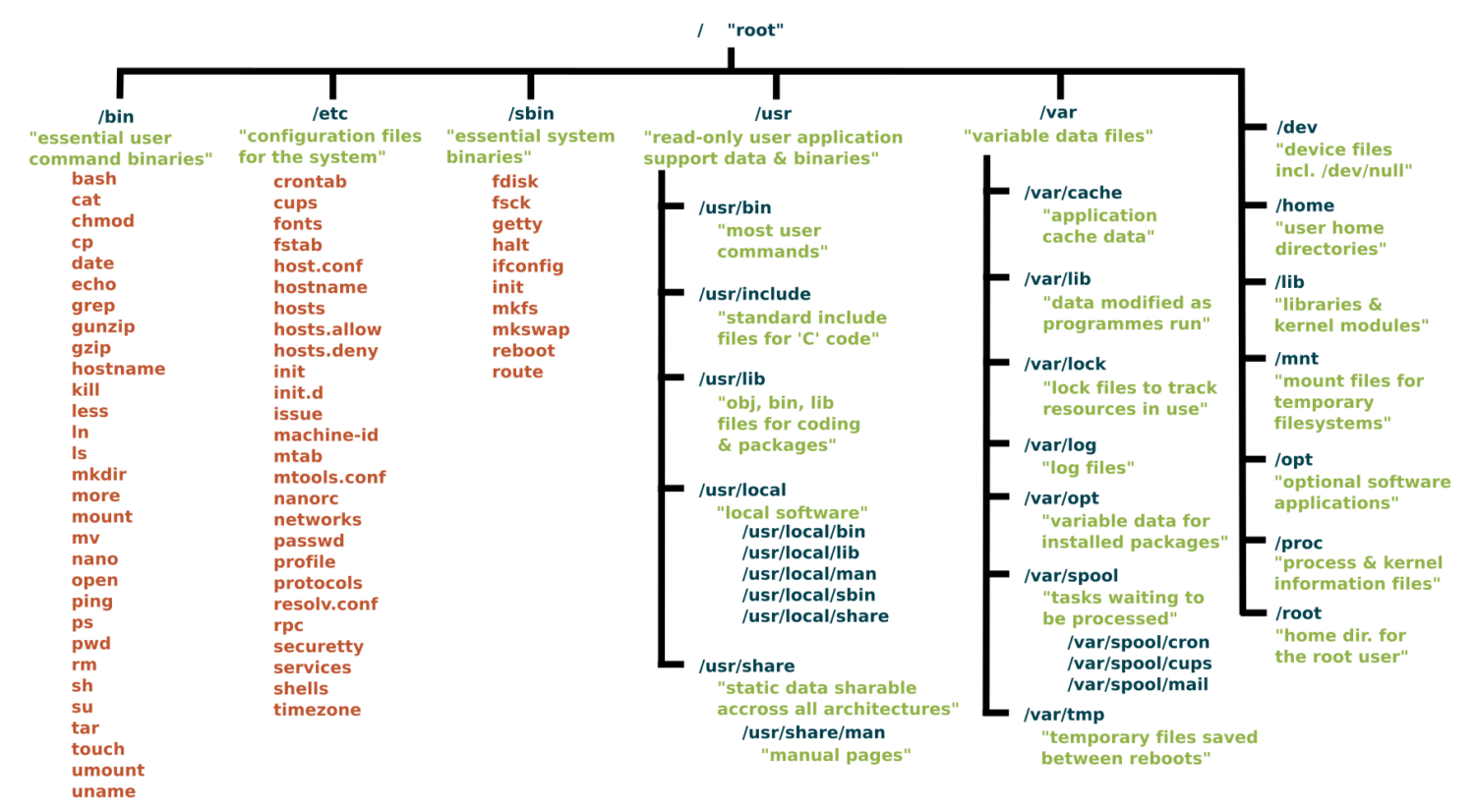

File Systems

File System Structure Essentials

A lot of DS and AI infrastructure runs on Linux/Unix type filesystems, including MacOS.

Root Directory (/):

The slash character represents the root of the entire file system.

Directory Conventions

/: The slash character by itself is the root of the filesystem/bin: A place containing programs that you can run/boot: A place containing the kernel and other pieces that allow your computer to start/dev: A place containing special files representing all your devices/etc: A place with lots of configuration information (i.e. login and password data)/home: All user's home directories/lib: A place for all system libraries/mnt: A place to mount external file systems/opt: A place to install user software/proc: Lots of information about your computer and what is running on it/sbin: Similar to bin but for the superuser/usr: Honestly a mishmash of things and rather overlapping with other directories/tmp: A place for temporary files that will be wiped out on a reboot/var: A place where many programs write files to maintain state

Key Directories You'll Use:

/ # Root of entire system

├── home/ # User home directories

│ └── username/ # Your personal space

├── usr/ # User programs and libraries

│ ├── bin/ # User programs (like cargo, rustc)

│ └── local/ # Locally installed software

└── tmp/ # Temporary files

Navigation Shortcuts:

~= Your home directory.= Current directory..= Parent directory/= Root directory

To explore further

You can read more about the Unix filesystem at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unix_filesystem.

The Linux shell

It is an environment for finding files, executing programs, manipulating (create, edit, delete) files and easily stitching multiple commands together to do something more complex.

Windows and MacOS has command shells, but Windows is not fully compatible, however MacOS command shell is.

Windows Subystem for Linux is fully compatible.

In Class Activity Part 1: Access/Install Terminal Shell

Directions for MacOS Users and Windows Users.

macOS Users:

Your Mac already has a terminal! Here's how to access it:

-

Open Terminal:

- Press

Cmd + Spaceto open Spotlight - Type "Terminal" and press Enter

- Or: Applications → Utilities → Terminal

- Press

-

Check Your Shell:

echo $SHELL # Modern Macs use zsh, older ones use bash -

Optional: Install Better Tools:

Install Homebrew (package manager for macOS)

/bin/bash -c "$(curl -fsSL https://raw.githubusercontent.com/Homebrew/install/HEAD/install.sh)"

Install useful tools

brew install tree # Visual directory structure

brew install ripgrep # Fast text search

Windows Users:

Windows has several terminal options. For this exercise we recommend Option 1, Git bash.

When you have more time, you might want to explore Windows Subsystem for Linux so you can have a full, compliant linux system accessible on Windows.

PowerShell aliases some commands to be Linux-like, but they are fairly quirky.

We recommend Git Bash or WSL:

-

Option A: Git Bash (Easier)

- Download Git for Windows from git-scm.com

- During installation, select "Use Git and optional Unix tools from the Command Prompt"

- Open "Git Bash" from Start menu

- This gives you Unix-like commands on Windows

-

Option B: Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL)

# Run PowerShell as Administrator, then: wsl --install # Restart your computer # Open "Ubuntu" from Start menu -

Option C: PowerShell (Built-in)

- Press

Win + Xand select "PowerShell" - Note: Commands differ from Unix (use

dirinstead ofls, etc.) - Not recommended for the in-class activities.

- Press

Verify Your Setup (Both Platforms)

pwd # Should show your current directory

ls # Should list files (macOS/Linux) or use 'dir' (PowerShell)

which ls # Should show path to ls command (if available)

echo "Hello!" # Should print Hello!

Essential Commands for Daily Use

Navigation and Exploration:

pwd # Show current directory path

ls # List files in current directory

ls -al # List files with details and hidden files

cd directory_name # Change to directory

cd .. # Go up one directory

cd ~ # Go to home directory

Creating and Organizing:

mkdir project_name # Create directory

mkdir -p path/to/dir # Create nested directories

touch filename.txt # Create empty file

cp file.txt backup.txt # Copy file

mv old_name new_name # Rename/move file

rm filename # Delete file

rm -r directory_name # Delete directory and contents

rm -rf directory_name # Delete dir and contents without confirmation

Viewing File Contents:

cat filename.txt # Display entire file

head filename.txt # Show first 10 lines

tail filename.txt # Show last 10 lines

less filename.txt # View file page by page (press q to quit)

File Permissions Made Simple

Understanding ls -l Output:

-rw-r--r-- 1 user group 1024 Jan 15 10:30 filename.txt

drwxr-xr-x 2 user group 4096 Jan 15 10:25 dirname

Permission Breakdown:

- First character:

-(file) ord(directory) - Next 9 characters in groups of 3:

- Owner permissions (rwx): read, write, execute

- Group permissions (r-x): read, no write, execute

- Others permissions (r--): read only

We will see these kinds of permissions again in Rust programming!

Common Permission Patterns:

644orrw-r--r--: Files you can edit, others can read755orrwxr-xr-x: Programs you can run, others can read/run600orrw-------: Private files only you can access

Pipes and Redirection Basics

Saving Output to Files:

ls > file_list.txt # Save directory listing to file

echo "Hello World" > notes.txt # Overwrite file contents

echo "It is me" >> notes.text # Append to file content

Combining Commands with Pipes:

ls | grep ".txt" # List only .txt files

cat file.txt | head -5 # Show first 5 lines of file

ls -l | wc -l # Count number of files in directory

Practical Examples:

# Find large files

ls -la | sort -k5 -nr | head -10

# Count total lines in all text files

cat *.txt | wc -l

# Search for pattern and save results

grep "error" log.txt > errors.txt

Setting Up for Programming

Creating Project Structure:

# Create organized development directory

# The '-p' means make intermediate directories as required

mkdir -p ~/projects/rust_projects

mkdir -p ~/projects/data_science

mkdir -p ~/projects/tools

# Navigate to project area

cd ~/projects/rust_projects

# Create specific project

mkdir my_first_rust_project

cd my_first_rust_project

Text Editors in the Shell

- It is often useful to edit files in the shell.

- The two most common text editors in the shell are

nanoandvim.nanois a simple text editor that is easy to use and has a minimal learning curve.vimis a more powerful text editor that is more difficult to learn but has a more powerful feature set.

See for example vim-hero.com for a tutorial on vim.

It is very helpful to learn minimal editing skills in one of these.

Customizing Your Shell Profile (Optional)

Understanding Shell Configuration Files:

Your shell reads a configuration file when it starts up. This is where you can add aliases, modify your PATH, and customize your environment.

Common Configuration Files:

- macOS (zsh):

~/.zshrc - macOS (bash):

~/.bash_profileor~/.bashrc - Linux (bash):

~/.bashrc - Windows Git Bash:

~/.bash_profile

Finding Your Configuration File:

It's in your Home directory.

# Check which shell you're using (MacOS/Linus)

echo $SHELL

# macOS with zsh

echo $HOME/.zshrc

# macOS/Linux with bash

echo $HOME/.bash_profile

echo $HOME/.bashrc

Adding Useful Aliases:

# Edit your shell configuration file (choose the right one for your system)

nano ~/.zshrc # macOS zsh

nano ~/.bash_profile # macOS bash or Git Bash

nano ~/.bashrc # Linux bash

# Add these helpful aliases:

alias ll='ls -la'

alias ..='cd ..'

alias ...='cd ../..'

alias projects='cd ~/projects'

alias rust-projects='cd ~/projects/rust_projects'

alias grep='grep --color=auto'

alias tree='tree -C'

# Custom functions

# This will make a directory specified as the argument and change into it

mkcd() {

mkdir -p "$1" && cd "$1"

}

Modifying Your PATH:

# Add to your shell configuration file

export PATH="$HOME/bin:$PATH"

export PATH="$HOME/.cargo/bin:$PATH" # For Rust tools (we'll add this later)

# For development tools

export PATH="/usr/local/bin:$PATH"

Applying Changes:

# Method 1: Reload your shell configuration

source ~/.zshrc # For zsh

source ~/.bash_profile # For bash

# Method 2: Start a new terminal session

# Method 3: Run the command directly

exec $SHELL

Useful Environment Variables:

# Add to your shell configuration file

export EDITOR=nano # Set default text editor

export HISTSIZE=10000 # Remember more commands

export HISTFILESIZE=20000 # Store more history

# Color support for ls

export CLICOLOR=1 # macOS

export LS_COLORS='di=34:ln=35:so=32:pi=33:ex=31:bd=34:cd=34:su=0:sg=0:tw=34:ow=34' # Linux

Shell Configuration with Git Branch Name

A useful shell configuration is modify the shell command prompt to show your current working directory and your git branch name if you are in a git project.

Bash Configuration

If you are using bash, follow the instructions for bash posted at DS549 Shell Configuraiton.

Zsh Configuration

If you are using zsh, which is the default shell on MacOS, you can paste the following

lines into your ~/.zshrc file to configure the shell prompt to show your current working directory and your git branch name if you are in a git project.

Perhaps the easiest way to edit if you have VS Code installed is to run the following command in the terminal:

code ~/.zshrc

Then copy and paste the following lines into the file:

# 1. Load the vcs_info module

autoload -Uz vcs_info

# 2. Configure vcs_info

# Enable check-for-changes (so it knows if files are modified)

zstyle ':vcs_info:*' check-for-changes true

zstyle ':vcs_info:*' unstagedstr '!' # Display ! if there are unstaged changes

zstyle ':vcs_info:*' stagedstr '+' # Display + if there are staged changes

# Set the format of the output

# %b = branch name

# %u = unstagedstr (from above)

# %c = stagedstr (from above)

zstyle ':vcs_info:git:*' formats '(%b%u%c)'

zstyle ':vcs_info:git:*' actionformats '(%b|%a%u%c)' # Used during rebase/merge

# 3. Use the precmd hook

# This function runs automatically before every prompt display

precmd() {

vcs_info

}

# 4. Set the prompt

# We use ${vcs_info_msg_0_} to grab the info generated by the function above

setopt PROMPT_SUBST

PROMPT='%(?.%F{green}√.%F{red}?%?)%f %B%F{240}%1~%f%b %F{red}${vcs_info_msg_0_}%f %# '

Make sure to delete any other lines that set the PROMPT variable that are not

part of the above script.

Shell scripts

A way to write simple programs using the linux commands and some control flow elements. Good for small things. Never write anything complicated using shell.

Shell Script File

Shell script files typically use the extension *.sh, e.g. script.sh.

Shell script files start with a shebang line, #!/bin/bash.

#!/bin/bash

echo "Hello world!"

To execute shell script you can use the command:

source script.sh

Hint: You can use the

nanotext editor to edit simple files like this.

In-Class Activity: Shell Challenge

Prerequisite: You should have completed Part I above to have access to a Linux or MacOS style shell.

Part 2: Scavenger Hunt

Complete the steps using only the command line!

You can use echo to write to the file, or text editor nano.

Feel free to reference the cheat sheet below and the notes above.

-

Create a directory called

treasure_huntin your course projects folder. -

In that directory create a file called

command_line_scavenger_hunt.txtthat contains the following:- Your name / group members

-

Run these lines and record the output into that

.txtfile:

whoami # What's your username?

hostname # What's your computer's name?

pwd # Where do you start?

echo $HOME # What's your home directory path?

-

Inside that directory, create a text file named

clue_1.txtwith the content "The treasure is hidden in plain sight" -

Create a subdirectory called

secret_chamber -

In the

secret_chamberdirectory, create a file calledclue_2.txtwith the content "Look for a hidden file" -

Create a hidden file in the

secret_chamberdirectory called.treasure_map.txtwith the content "Congratulations. You found the treasure" -

When you're done, change to the parent directory of

treasure_huntand run the commandzip -r treasure_hunt.zip treasure_hunt.- Or if you are on Git Bash, you may have to use the command

tar.exe -a -c -f treasure_hunt.zip treasure_hunt

- Or if you are on Git Bash, you may have to use the command

-

Upload

treasure_hunt.zipto gradescope - next time we will introduce git and github and use that platform going forward. -

Optional: For Bragging Rights Create a shell script that does all of the above commands and upload that to Gradescope as well.

Command Line Cheat Sheet

Basic Navigation & Listing

Mac/Linux (Bash/Zsh):

# Navigate directories

cd ~ # Go to home directory

cd /path/to/directory # Go to specific directory

pwd # Show current directory

# List files and directories

ls # List files

ls -la # List all files (including hidden) with details

ls -lh # List with human-readable file sizes

ls -t # List sorted by modification time

Windows (PowerShell/Command Prompt):

# Navigate directories

cd ~ # Go to home directory (PowerShell)

cd %USERPROFILE% # Go to home directory (Command Prompt)

cd C:\path\to\directory # Go to specific directory

pwd # Show current directory (PowerShell)

cd # Show current directory (Command Prompt)

# List files and directories

ls # List files (PowerShell)

dir # List files (Command Prompt)

dir /a # List all files including hidden

Get-ChildItem -Force # List all files including hidden (PowerShell)

Finding Files

Mac/Linux:

# Find files by name

find /home -name "*.pdf" # Find all PDF files in /home

find . -type f -name "*.log" # Find log files in current directory

find /usr -type l # Find symbolic links

# Find files by other criteria

find . -type f -size +1M # Find files larger than 1MB

find . -mtime -7 # Find files modified in last 7 days

find . -maxdepth 3 -type d # Find directories up to 3 levels deep

Windows:

# PowerShell - Find files by name

Get-ChildItem -Path C:\Users -Filter "*.pdf" -Recurse

Get-ChildItem -Path . -Filter "*.log" -Recurse

dir *.pdf /s # Command Prompt - recursive search

# Find files by other criteria

Get-ChildItem -Recurse | Where-Object {$_.Length -gt 1MB} # Files > 1MB

Get-ChildItem -Recurse | Where-Object {$_.LastWriteTime -gt (Get-Date).AddDays(-7)} # Last 7 days

Counting & Statistics

Mac/Linux:

# Count files

find . -name "*.pdf" | wc -l # Count PDF files

ls -1 | wc -l # Count items in current directory

# File and directory sizes

du -sh ~/Documents # Total size of Documents directory

du -h --max-depth=1 /usr | sort -rh # Size of subdirectories, largest first

ls -lah # List files with sizes

Windows:

# Count files (PowerShell)

(Get-ChildItem -Filter "*.pdf" -Recurse).Count

(Get-ChildItem).Count # Count items in current directory

# File and directory sizes

Get-ChildItem -Recurse | Measure-Object -Property Length -Sum # Total size

dir | sort length -desc # Sort by size (Command Prompt)

Text Processing & Search

Mac/Linux:

# Search within files

grep -r "error" /var/log # Search for "error" recursively

grep -c "hello" file.txt # Count occurrences of "hello"

grep -n "pattern" file.txt # Show line numbers with matches

# Count lines, words, characters

wc -l file.txt # Count lines

wc -w file.txt # Count words

cat file.txt | grep "the" | wc -l # Count lines containing "the"

Windows:

# Search within files (PowerShell)

Select-String -Path "C:\logs\*" -Pattern "error" -Recurse

(Select-String -Path "file.txt" -Pattern "hello").Count

Get-Content file.txt | Select-String -Pattern "the" | Measure-Object

# Command Prompt

findstr /s "error" C:\logs\* # Search for "error" recursively

find /c "the" file.txt # Count occurrences of "the"

System Information

Mac/Linux:

# System stats

df -h # Disk space usage

free -h # Memory usage (Linux)

system_profiler SPHardwareDataType # Hardware info (Mac)

uptime # System uptime

who # Currently logged in users

# Process information

ps aux # List all processes

ps aux | grep chrome # Find processes containing "chrome"

ps aux | wc -l # Count total processes

Windows:

# System stats (PowerShell)

Get-WmiObject -Class Win32_LogicalDisk | Select-Object Size,FreeSpace

Get-WmiObject -Class Win32_ComputerSystem | Select-Object TotalPhysicalMemory

(Get-Date) - (Get-CimInstance Win32_OperatingSystem).LastBootUpTime # Uptime

Get-LocalUser # User accounts

# Process information

Get-Process # List all processes

Get-Process | Where-Object {$_.Name -like "*chrome*"} # Find chrome processes

(Get-Process).Count # Count total processes

# Command Prompt alternatives

wmic logicaldisk get size,freespace # Disk space

tasklist # List processes

tasklist | find "chrome" # Find chrome processes

File Permissions & Properties

Mac/Linux:

# File permissions and details

ls -l filename # Detailed file information

stat filename # Comprehensive file statistics

file filename # Determine file type

# Find files by permissions

find . -type f -readable # Find readable files

find . -type f ! -executable # Find non-executable files

Windows:

# File details (PowerShell)

Get-ItemProperty filename # Detailed file information

Get-Acl filename # File permissions

dir filename # Basic file info (Command Prompt)

# File attributes

Get-ChildItem | Where-Object {$_.Attributes -match "ReadOnly"} # Read-only files

Network & Hardware

Mac/Linux:

# Network information

ip addr show # Show network interfaces (Linux)

ifconfig # Network interfaces (Mac/older Linux)

networksetup -listallhardwareports # Network interfaces (Mac)

cat /proc/cpuinfo # CPU information (Linux)

system_profiler SPHardwareDataType # Hardware info (Mac)

Windows:

# Network information (PowerShell)

Get-NetAdapter # Network interfaces

ipconfig # IP configuration (Command Prompt)

Get-WmiObject Win32_Processor # CPU information

Get-ComputerInfo # Comprehensive system info

Platform-Specific Tips

Mac/Linux Users:

- Your home directory is

~or$HOME - Hidden files start with a dot (.)

- Use

man commandfor detailed help - Try

which commandto find where a command is located

Windows Users:

- Your home directory is

%USERPROFILE%(Command Prompt) or$env:USERPROFILE(PowerShell) - Hidden files have the hidden attribute (use

dir /ahto see them) - Use

Get-Help commandin PowerShell orhelp commandin Command Prompt for detailed help - Try

where commandto find where a command is located

Universal Tips:

- Use Tab completion to avoid typing long paths

- Most shells support command history (up arrow or Ctrl+R)

- Combine commands with pipes (

|) to chain operations - Search online for "[command name] [your OS]" for specific examples

Hello Git!

About This Module

This module introduces version control concepts and Git fundamentals for individual development workflow. You'll learn to track changes, create repositories, and use GitHub for backup and sharing. This foundation prepares you for collaborative programming and professional development practices.

Prework

Read or at least skim through Chapter 1: Getting Started, Chapter 2, 2.1-2.5 and Section 3.1. Don't worry if you don't fully understand the concepts, we'll cover them in class.

If you're on Windows, install git from

https://git-scm.com/downloads.

You probably already did this to use git-bash for the Shell class activity.

MacOS comes pre-installed with git.

From your Home or projects directory in a terminal or cmd, run the command:

git clone https://github.com/cdsds210/simple-repo.git

If it is the first time, it may ask you to login or authenticate with GitHub.

Ultimately, you want to cache your GitHub credentials locally on your computer so you don't have to login every time. We suggest you do this with the GitHub CLI.

Some other resources you might find helpful:

- GitHub's Git Handbook - Core concepts overview

- Git Commands Cheat Sheet

Pre-lecture Reflections

Before class, consider these questions:

-

Snapshots vs. Differences Most version control systems store information as a list of file-based changes (deltas). How does Git store data differently, and how does it handle files that haven't changed between commits?

-

The Three States Git files reside in one of three main states: modified, staged, and committed. Describe what each state represents in the workflow. Specifically, what is the purpose of the "staging area" (or index) before a commit is finalized?

-

Local vs. Centralized Operations In a Centralized Version Control System (CVCS), operations often rely on a connection to a central server. How does Git’s nature as a Distributed Version Control System (DVCS) differ regarding offline work and speed?

-

Integrity and Identity Git generates a 40-character string (SHA-1 hash) for every commit and file. Why does Git do this, and what does it prevent from happening to your project's history without you knowing?

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, you should be able to:

- Understand why version control is critical for programming

- Configure Git for first-time use

- Create repositories and make meaningful commits

- Connect local repositories to GitHub

- Use the basic Git workflow for individual projects

- Recover from common Git mistakes

You may want to follow along with the git commands in your own environment during the lecture.

Why Version Control Matters

The Problem Without Git:

my_project.rs

my_project_backup.rs

my_project_final.rs

my_project_final_REALLY_FINAL.rs

my_project_broken_trying_to_fix.rs

my_project_working_maybe.rs

The Solution With Git:

git log --oneline

a1b2c3d Fix input validation bug

e4f5g6h Add error handling for file operations

h7i8j9k Implement basic calculator functions

k1l2m3n Initial project setup

Key Benefits:

- Never lose work: Complete history of all changes

- Fearless experimentation: Try new ideas without breaking working code

- Clear progress tracking: See exactly what changed and when

- Professional workflow: Essential skill for any programming job

- Backup and sharing: Store code safely in the cloud

Core Git Concepts

Repository (Repo): A folder tracked by Git, containing your project and its complete history.

Commit: A snapshot of your project at a specific moment, with a message explaining what changed.

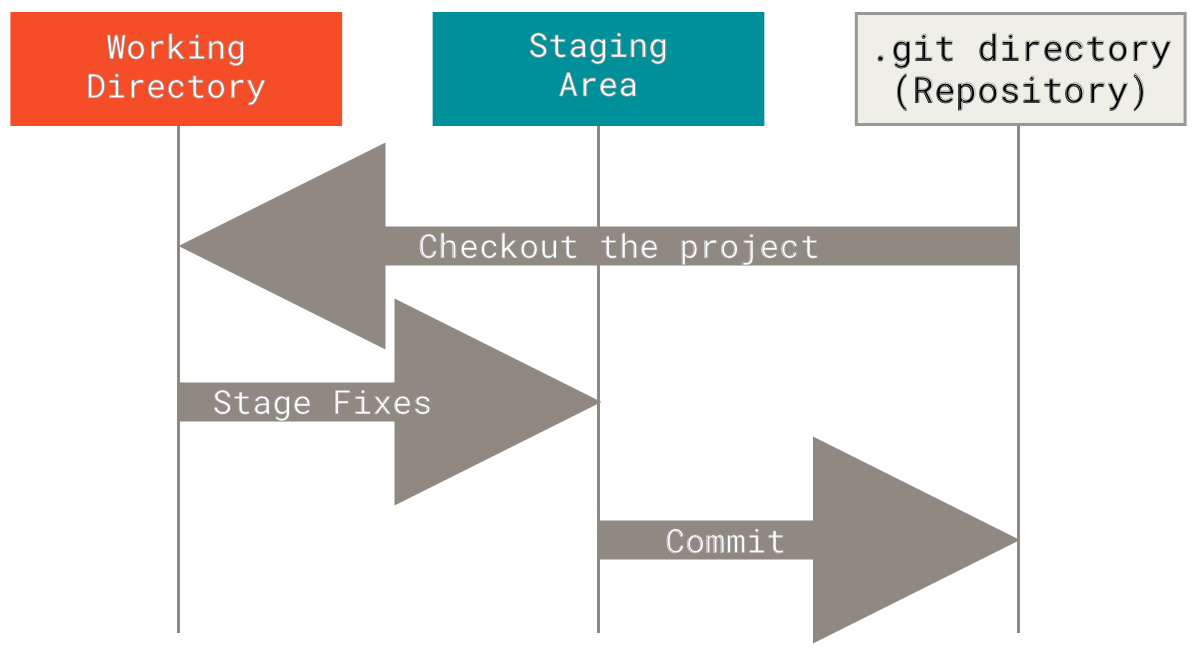

The Three States:

- Working Directory: Files you're currently editing

- Staging Area: Changes prepared for next commit

- Repository: Committed snapshots stored permanently

The Basic Workflow:

Edit files → Stage changes → Commit snapshot

(add) (commit)

Push: Uploads your local commits to a remote repository (like GitHub). Takes your local changes and shares them with others.

Local commits → Push → Remote repository

Pull: Downloads commits from a remote repository and merges them into your current branch. Gets the latest changes from others.

Remote repository → Pull → Local repository (updated)

Merge: Combines changes from different branches. Takes commits from one branch and integrates them into another branch.

Feature branch + Main branch → Merge → Combined history

Pull Request (PR): A request to merge your changes into another branch, typically used for code review. You "request" that someone "pull" your changes into the main codebase.

Your branch → Pull Request → Review → Merge into main branch

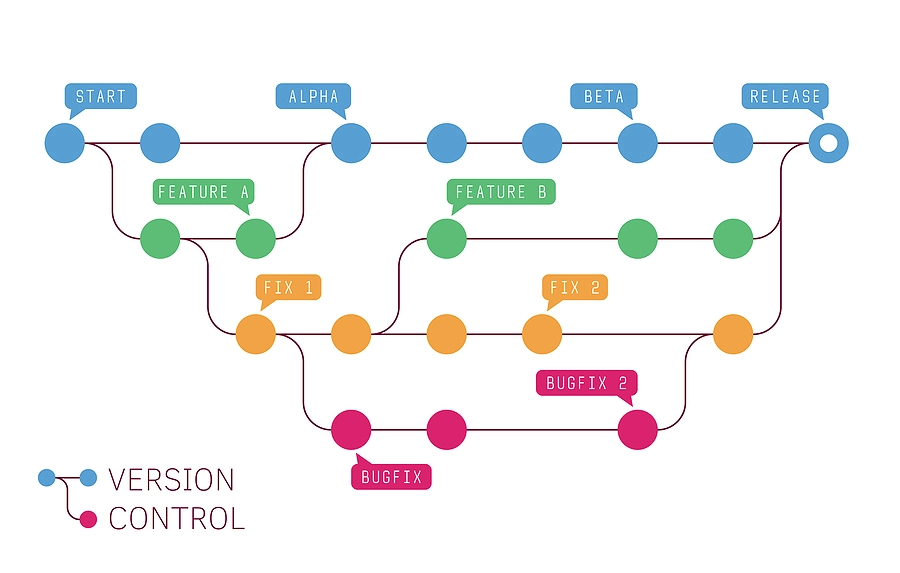

Git Branching

Lightweight Branching:

Git's key strength is efficient branching and merging:

- Main branch: Usually called

main(ormasterin older repos) - Feature branches: Created for new features or bug fixes

Branching Benefits:

- Isolate experimental work

- Enable parallel development

- Facilitate code review process

- Support different release versions

Essential Git Commands

Here are some more of those useful shell commands!

One-Time Setup

# Configure your identity (use your real name and email)

git config --global user.name "Your Full Name"

git config --global user.email "your.email@example.com"

If you don't want to publish your email in all your commits on GitHub, then highly recommended to get a "no-reply" email address from GitHub. Here are directions.

# Set default branch name

git config --global init.defaultBranch main

Note: The community has moved away from

masteras the default branch name, but it may still be default in some installations.

# Verify configuration

git config list # local configuration

git config list --global # global configuration

Starting a New Project

# Create project directory

mkdir my_rust_project

cd my_rust_project

# Initialize Git repository

git init

# Check status

git status

Daily Git Workflow (without GithHub)

# Create a descriptive branch name for the change you want to make

git checkout -b topic_branch

# Check what's changed

git status # See current state

git diff # See specific changes

# make edits to, for example filename.rs

# Stage changes for commit

git add filename.rs # Add specific file

git add . # Add all changes in current directory

# Create commit with a comment

git commit -m "Add calculator function"

# View history

git log # Full commit history

git log --oneline # Compact view

# View branches

git branch

# Switch back to main

git checkout main

# Merge topic branch back into main

git merge topic_branch

# Delete the topic branch when finished

git branch -d topic_branch

Writing Good Commit Messages

The Golden Rule: Your commit message should complete this sentence: "If applied, this commit will [your message here]"

Good Examples:

git commit -m "Add input validation for calculator"

git commit -m "Fix division by zero error"

git commit -m "Refactor string parsing for clarity"

git commit -m "Add tests for edge cases"

Bad Examples:

git commit -m "stuff" # Too vague

git commit -m "fixed it" # What did you fix?

git commit -m "more changes" # Not helpful

git commit -m "asdfjkl" # Meaningless

Commit Message Guidelines:

- Start with a verb: Add, Fix, Update, Remove, Refactor

- Be specific: What exactly did you change?

- Keep it under 50 characters for the first line

- Use present tense: "Add function" not "Added function"

Working with GitHub

Why GitHub?

- Remote backup: Your code is safe in the cloud

- Easy sharing: Share projects with instructors and peers

- Portfolio building: Showcase your work to employers

- Collaboration: Essential for team projects

Connecting to GitHub:

# Create repository on GitHub first (via web interface)

# Then connect your local repository:

git remote add origin https://github.com/yourusername/repository-name.git

git branch -M main

git push -u origin main

Note: The above instructions are provided to you by GitHub when you create an empty repository.

Git Remote Server (GitHub) Related Command

# Check remote connection

git remote -v

# Clone existing repository

git clone https://github.com/username/repository.git

cd repository

# Pull any changes from GitHub

git pull

# Push your commits to GitHub

git push

Daily GitHub Workflow

# Create a descriptive branch name for the change you want to make

git checkout -b topic_branch

# Check what's changed

git status # See current state

git diff # See specific changes

# make edits to, for example filename.rs

# Stage changes for commit

git add filename.rs # Add specific file

git add . # Add all changes in current directory

# Create commit with a comment

git commit -m "Add calculator function"

# View history

git log # Full commit history

git log --oneline # Compact view

# View branches

git branch

# Run local validation tests on changes

# Push to GitHub

git push origin topic_branch

# Create a Pull Request on GitHub

# Repeat above to make any changes from PR review comments

# When done, merge PR to main on GitHub

git checkout main

git pull

# Delete the topic branch when finished

git branch -d topic_branch

Git for Homework

Recommended Workflow:

Updated Jan 27, 2026 to reflect workflow with GitHub Classroom.

# Clone assignment from GitHub classroom.

git clone <repo-URL>

# Create and checkout a new development branch

git branch q1

git checkout q1

# Alternatively, you can combine these steps into one:

git checkout -b q1 # create and checkout a new branch called q1

# Work and commit frequently

# ... write some code for example in src/main.rs...

git add src/main.rs

git commit -m "Implement basic data structure"

# ... write more code ...

git add src/main.rs

git commit -m "Add error handling"

# Push your commits to GitHub

git push -u origin q1

# As practice, we want you to create a pull request on GitHub, then merge

# that pull request into the main branh on github.

# So now you have commits merged to main on GitHub that is not reflected locally

git checkout main # switch to main branch

git pull # pull down all your remote changes

# Now you are ready to checkout a new development branch

Best Practices for This Course:

- Commit early and often: We expect to see a minimum of 3-5 commits per assignment

- One logical change per commit: Each commit should make sense on its own

- Meaningful progression: Your commit history should tell the story of your solution

- Clean final version: Make sure your final commit has working, clean code

Common Git Scenarios

"I made a mistake in my last commit message"

git commit --amend -m "Corrected commit message"

"I forgot to add a file to my last commit"

git add forgotten_file.rs

git commit --amend --no-edit

"I want to undo changes I haven't committed yet"

git checkout -- filename.rs # Undo changes to specific file

git reset --hard HEAD # Undo ALL uncommitted changes (CAREFUL!)

"I want to see what changed in a specific commit"

git show commit_hash # Show specific commit

git log --patch # Show all commits with changes

Understanding .gitignore

What NOT to Track: Some files should never be committed to Git:

# Rust build artifacts

/target/

# IDE files

.vscode/settings.json

.idea/

*.swp

# OS files

.DS_Store

Thumbs.db

# Personal notes

notes.txt

TODO.md

Creating .gitignore:

# Create .gitignore file

touch .gitignore

# Edit with your preferred editor to add patterns above

# Commit the .gitignore file

git add .gitignore

git commit -m "Add .gitignore for Rust project"

Resources for learning more and practicing

- A gamified tutorial for the basics: https://ohmygit.org/

- Interactive online Git tutorial that goes a bit deper: https://learngitbranching.js.org/

- Another good tutorial (examples in ruby): https://gitimmersion.com/

- Pro Git book (free online): https://git-scm.com/book/en/v2

You'll be using another learning app for HW1.ß

GitHub Collaboration Challenge

Form teams of three people.

Follow these instructions with your teammates to practice creating a GitHub repository, branching, pull requests (PRs), review, and merging. Work in groups of three—each person will create and review a pull request.

1. Create and clone the repository (≈3 min)

- Choose one teammate to act as the repository lead.

- They should log in to GitHub, click the “+” menu in the upper‑right and select New repository.

- Call the repository "github-class-challenge", optionally add a description, make the visibility public, check “Add a README,” and

- click Create repository.

- Go to Settings/Collaborators and add your teammates as developers with write access.

- Each team member needs a local copy of the repository. On the repo’s main page, click Code, copy the HTTPS URL, open a terminal, navigate to the folder where you want the project, and run:

git clone <repo‑URL>

Cloning creates a full local copy of all files and history.

2. Create your own topic branch (≈2 min)

A topic branch lets you make changes without affecting the default main branch. GitHub recommends using a topic branch when making a pull request.

On your local machine:

git checkout -b <your‑first‑name>-topic

git push -u origin <your‑first‑name>-topic # creates the branch on GitHub

Pick a branch name based on your first name (for example alex-topic).

3. Add a personal file, commit and push (≈5 min)

-

In your cloned repository (on your topic branch), create a new text file named after yourself—e.g.,

alex.txt. Write a few sentences about yourself (major, hometown, a fun fact). -

Stage and commit the file:

git add alex.txt git commit -m "Add personal bio"Good commit messages explain what changed.

-

Push your commit to GitHub:

git push

4. Create a pull request (PR) for your teammates to review (≈3 min)

- On GitHub, click Pull requests → New pull request.

- Set the base branch to

mainand the compare branch to your topic branch. - Provide a clear title (e.g. “Add Alex’s bio”) and a short description of what you added. Creating a pull request lets your collaborators review and discuss your changes before merging them.

- Request reviews from your two teammates.

5. Review your teammates’ pull requests (≈4 min)

- Open each of your teammates’ PRs.

- On the Conversation or Files changed tab, leave at least one constructive comment (ask a question or suggest something you’d like them to add). You can comment on a specific line or leave a general comment.

- Submit your review with the Comment option. Pull request reviews can be comments, approvals, or requests for changes; you’re only commenting at this stage.

6. Address feedback by making another commit (≈3 min)

-

Read the comments on your PR. Edit your text file locally in response to the feedback.

-

Stage, commit, and push the changes:

git add alex.txt git commit -m "Address feedback" git pushAny new commits you push will automatically update the open pull request.

-

Reply to the reviewer’s comment in the PR, explaining how you addressed their feedback.

7. Approve and merge pull requests (≈3 min)

- After each PR author has addressed the comments, revisit the PRs you reviewed.

- Click Review changes → Approve to approve the updated PR.

- Once a PR has at least one approval, a teammate other than the author should merge it.

-In the PR, scroll to the bottom and click Merge pull request, then Confirm merge. - Delete the topic branch when prompted; keeping the branch list tidy is good practice.

Each student should merge one of the other students’ PRs so everyone practices.

8. Capture a snapshot for submission (≈3 min)

- One teammate downloads a snapshot of the final repository. On the repo’s main page, click Code → Download ZIP. GitHub generates a snapshot of the current branch or commit.

- Open the Commits page (click the “n commits” link) and take a screenshot showing the commit history.

- Go to Pull requests → Closed, and capture a screenshot showing the three closed PRs and their approval status. You can also use the Activity view to see a detailed history of pushes, merges, and branch changes.

- Upload the ZIP file and screenshots to Gradescope.

Tips

- Use descriptive commit messages and branch names.

- Each commit is a snapshot; keep commits focused on a single change.

- Be polite and constructive in your feedback.

- Delete merged branches to keep your repository clean.

This exercise walks you through the entire GitHub flow—creating a repository, branching, committing, creating a PR, reviewing, addressing feedback, merging, and capturing a snapshot. Completing these steps will help you collaborate effectively on future projects.

Hello Rust!

About This Module

This module provides your first hands-on experience with Rust programming. You'll write actual programs, understand basic syntax, and see how Rust's compilation process works. We'll focus on building confidence through practical programming while comparing key concepts to Python.

Prework

Prework Readings

Review this module.

Read the following Rust basics:

- The Rust Programming Language - Chapter 1.2: Hello, World!

- The Rust Programming Language - Chapter 1.3: Hello, Cargo!

Optionally browse:

Pre-lecture Reflections

Before class, consider these questions:

- How does compiling code differ from running Python scripts directly?

- What might be the advantages of catching errors before your program runs?

- How does Rust's

println!macro compare to Python'sprint()function? - Why might explicit type declarations help prevent bugs?

- What challenges might you face transitioning from Python's flexibility to Rust's strictness?

Topics

- Installing Rust

- Compiled vs Interpretted Languages

- Write and compile our first simple program

Installing Rust

Before we can write Rust programs, we need to install Rust on your system.

From https://www.rust-lang.org/tools/install:

On MacOS:

# Install Rust via rustup

curl --proto '=https' --tlsv1.2 -sSf https://sh.rustup.rs | sh

Question: can you interpret the shell command above?

On Windows:

Download and run rustup-init.exe (64-bit).

It will ask you some questions.

Download Visual Studio Community Edition Installer.

Open up Visual Studio Community Edition Installer and install the C++ core

desktop features.

Verify Installation

From MacOS terminal or Windows CMD or PowerShell

rustc --version # Should show Rust compiler version

cargo --version # Should show Cargo package manager version

rustup --version # Should show Rustup toolchain installer version

Troubleshooting Installation:

# Update Rust if already installed

rustup update

# Check which toolchain is active

rustup show

# Reinstall if needed (a last resort!!)

rustup self uninstall

# Then reinstall following installation steps above

Write and compile simple Rust program

Generally you would create a project directory for all your projects and then a subdirectory for each project.

Follow along now if you have Rust installed, or try at your first opportunity later.

$ mkdir ~/projects

$ cd ~/projects

$ mkdir hello_world

$ cd hello_world

All Rust source files have the extension .rs.

Create and edit a file called main.rs.

For example with the nano editor on MacOS

# From MacoS terminal

nano main.rs

or notepad on Windows

# From Windows CMD or PowerShell

notepad main.rs

and add the following code:

fn main() { println!("Hello, world!"); }

Note: Since our course notes are in

mdbook, code cells like above can be executed right from the notes!In many cases we make the code cell editable right on the web page!

If you created that file on the command line, then you compile and run the program with the following commands:

$ rustc main.rs # compile with rustc which creates an executable

If it compiled correctly, you should have a new file in your directory

For example on MacOS or Linux you might see:

hello_world % ls -l

total 880

-rwxr-xr-x 1 tgardos staff 446280 Sep 10 21:03 main

-rw-r--r-- 1 tgardos staff 45 Sep 10 21:02 main.rs

Question: What is the new file? What do you observe about the file properties?

On Windows you'll see main.exe.

$ ./main # run the executable

Hello, world!

Compiled (e.g. Rust) vs. Interpreted (e.g. Python)

Python: One Step (Interpreted)

python hello.py

- Python reads your code line by line and executes it immediately

- No separate compilation step needed

Rust: Two Steps (Compiled)

# Step 1: Compile (translate to machine code)

rustc hello.rs

# Step 2: Run the executable

./hello

rustcis your compilerrustctranslates your entire program to machine code- Then you run the executable (why

./?)

The main() function

fn main() { ... }

is how you define a function in Rust.

The function name main is reserved and is the entry point of the program.

The println!() Macro

Let's look at the single line of code in the main function:

println!("Hello, world!");Rust convention is to indent with 4 spaces -- never use tabs!!

println!is a macro which is indicated by the!suffix.- Macros are functions that are expanded at compile time.

- The string

"Hello, world!"is passed as an argument to the macro.

The line ends with a ; which is the end of the statement.

More Printing Tricks

Let's look at a program that prints in a bunch of different ways.

// A bunch of the output routines fn main() { let x = 9; let y = 16; print!("Hello, DS210!\n"); // Need to include the newline character println!("Hello, DS210!\n"); // The newline character here is redundant println!("{} plus {} is {}", x, y, x+y); // print with formatting placeholders //println!("{x} plus {y} is {x+y}"); // error: cannot use `x+y` in a format string println!("{x} plus {y} is {}\n", x+y); // but you can put variable names in the format string }

More on println!

- first parameter is a format string

{}are replaced by the following parameters

print! is similar to println! but does not add a newline at the end.

To dig deeper on formatting strings:

fmtmodule- Format strings syntax

Input Routines

Here's a fancier program. You don't have to worry about the details, but

paste it into a file name.rs, run rustc name.rs and then ./name.

// And some input routines

// So this is for demo purposes

use std::io;

use std::io::Write;

fn main() {

let mut user_input = String::new();

print!("What's your name? ");

io::stdout().flush().expect("Error flushing"); // flush the output and print error if it fails

let _ =io::stdin().read_line(&mut user_input); // read the input and store it in user_input

println!("Hello, {}!", user_input.trim());

}Project manager: cargo

Rust comes with a very helpful project and package manager: cargo

-

create a project:

cargo new PROJECT-NAME- creates a new directory with the project name and initializes git

- you can rename branch name from

mastertomainby runninggit branch -m master main

-

main file will be

PROJECT-NAME/src/main.rs -

cd PROJECT-NAMEto go into the project directory -

to run:

cargo run- compiles and runs the program

-

to just build:

cargo build

Cargo example

~ % cd ~/projects

projects % cargo new cargo-hello

Creating binary (application) `cargo-hello` package

note: see more `Cargo.toml` keys and their definitions at https://doc.rust-lang.org/cargo/reference/manifest.html

projects % cd cargo-hello

cargo-hello % tree

.

├── Cargo.toml

└── src

└── main.rs

2 directories, 2 files

cargo-hello % cargo run

Compiling cargo-hello v0.1.0 (/Users/tgardos/projects/cargo-hello)

Finished `dev` profile [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 0.21s

Running `target/debug/cargo-hello`

Hello, world!

% tree -L 3

.

├── Cargo.lock

├── Cargo.toml

├── src

│ └── main.rs

└── target

├── CACHEDIR.TAG

└── debug

├── build

├── cargo-hello

├── cargo-hello.d

├── deps

├── examples

└── incremental

8 directories, 6 files

Cargo --release

By default, cargo makes a slower debug build that has extra

debugging information.

We'll see more about that later.

Add --release to create a "fully optimized" version:

- longer compilation

- faster execution

- some runtime checks not included (e.g., integer overflow)

- debuging information not included

- the executable in a different folder

cargo-hello (master) % cargo build --release

Compiling cargo-hello v0.1.0 (/Users/tgardos/projects/cargo-hello)

Finished `release` profile [optimized] target(s) in 0.38s

(.venv) √ cargo-hello (master) % tree -L 2

.

├── Cargo.lock

├── Cargo.toml

├── src

│ └── main.rs

└── target

├── CACHEDIR.TAG

├── debug

└── release

5 directories, 4 files

Cargo check

If you just want to check if your current version compiles: cargo check

- Much faster for big projects

Hello Rust Activity

-

Get in groups of 3+

-

Place the lines of code in order in two parts on the page: your shell, and your code file

main.rsto make a reasonable sequence and functional code.

git branch -m master main

println!("Hello, world!");

cargo run

git push -u origin main

cargo new hello_world

nano src/main.rs

cd hello_world

fn main() {

git add src/main.rs

ls -la

git commit -m "Initial commit"

}

Overview of Programming languages

Learning Objectives

- Programming languages

- Describe the differences between a high level and low level programming language

- Describe the differences between an interpreted and compiled language

- Describe the differences between a static and dynamically typed language

- Know that there are different programming paradigms such as imperative and functional

- Describe the different memory management techniques

- Be able to identify the the properties of a particular language such as rust.

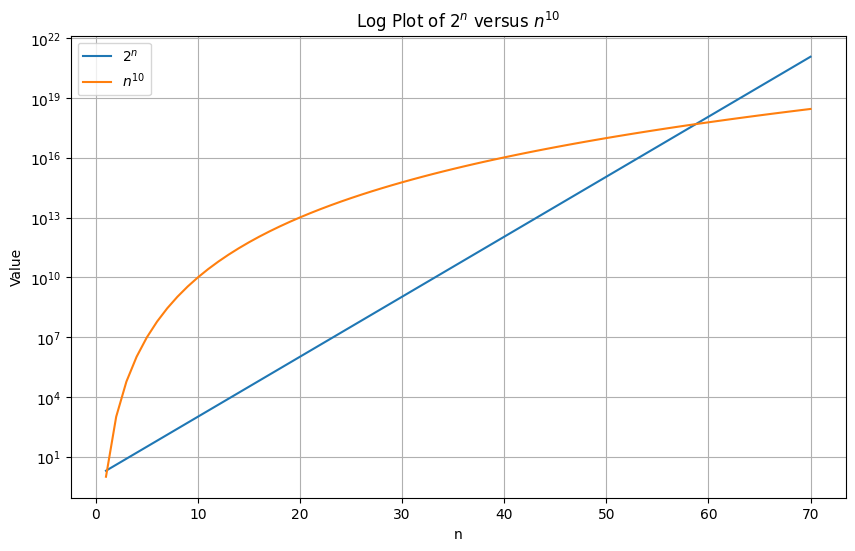

Various Language Levels

-