Rust Variables and Types

or how I learned to stop worrying and love the types1

Lecture 5: Monday, February 2, 2026, and

Lecture 6: Wednesday, February 4, 2026, and

Lecture 7: Friday, February 6, 2026.

Code examples

Rust is a statically typed programming language! Every variable must have its type known at compile time. This is a stark difference from Python, where a variable can take on different values from different types dynamically.

This has some really deep consequences that differentiate programming in Rust from that in Python.

To illustrate this better, let's start with a simple motivating example from Python.

Motivating example

Let's start with the following simple example from Python. Let's say we have two Python lists names and grades.

The first stores the names of different students in a class. The second one stores their grades. These lists are index-aligned:

the student whose name is at names[i] has grade grades[i].

names = ["Kinan", "Matt", "Taishan", "Zach", "Kesar", "Lingie", "Emir"]

grades = [ 0, 100, 95, 88, 99, 98, 97]

# Kinan's grade is 0, Kesar's grade is 99

Now, imagine we need to write some Python code to print the grade of a student given their name. Let's say the name

of this target student is stored in a variable called target.

# Alternatively, the value of target might be provided by the

# user, e.g., via some nice UI

target = "Kesar"

Our first observation is that the grades and names are index-aligned. So to find the grade of "Kesar",

we need to find the index of "Kesar" in names. Let's do that using a helper function. Here's a reasonable first attempt:

def find_index(target, names):

# iterate from 0 up to the length of names.

for i in range(len(names)):

if target == names[i]:

return i

Now, we can use find_index to retrieve the grade of "Kesar" as follows.

target = "Kesar"

index = find_index(target, names)

print(grades[index])

This indeed works! and if we run it, we will see the correct output.

99

The code will also work for many other values of target, e.g. "Kinan", "Matt", "Emir", etc.

However, what about if we search for a target who is not in names? For example target = tom?

In this case, find_index never finds a name equal to target, and so its for loop finishes without ever returning any i.

def find_index(target, names):

for i in range(len(names)):

# when target = 'Tom'

# then this condition is False for all elements in names

if target == names[i]:

# this is never reached for target = 'Tom'

return i

# instead, when target='Tom' the execution reachs this point.

# What should we return here?

return ?????

A good follow up question is what should find_index return in such a case?

Discuss this with your neighbor and come up with a candidate value!

Option 1: return -1

Many languages, e.g., Java, use -1 to indicate having not found something. Let's consider what happens

if we try that out in our Python example. In this case, our find_index function becomes:

def find_index(target, names):

for i in range(len(names)):

if target == names[i]:

return i

return -1

So what would happen in this case if we search for a target that does not exist?

target = "Tom"

index = find_index(target, names)

print(grades[index])

In this case, find_index returns -1. So, index is equal to -1, and we print grades[-1]. In python, an index of -1

corresponds to the last element in the list. So, our program will print the last grade in the list.

97

This is no good! Tom's grade is not 97! That's Emir's grade. In fact, Tom has no grade at all!!! This kind of silent problem is the worst kind you can have, because you may not even realize that it is a problem. Imagine if there were thousands of students. You run the code and see this output. You may not realize that the target you were looking for isn't there (or that you made a typo the student's name), and think that the output is accurate!

You can find the code for this option here.

Option 2: return "Not found"

A different option would be to return "Not found" or some special kind of similar message.

This is curious! find_index now sometimes returns an index (which is a number, i.e., of type int), and sometimes returns a string (in Python, that type is called str)!

def find_index(target, names):

for i in range(len(names)):

if target == names[i]:

return i

return "Not found"

target = "Tom"

index = find_index(target, names)

print(grades[index])

In this case, index is equal to `"Not found". So, our last line is equivalent to saying:

grades["Not found"]

This makes no sense! Imagine someone asks you to look up an element in a list at position "Not found", or position "hello!", or any other string. What would you do? I would freak out. So does Python, running this code results in the following error:

TypeError: list indices must be integers or slices, not str

In my opinion, this is a little better than option 1. At least, it is visible and obvious that something wrong went on. But it is still not good.

You can find the code for this option here.

Option 3: return "Not found" then manually check the type

How about we check the type of whatever find_index returns before we attempt to access the list of grades?

It turns out we can ask Python to tell us what type a variable (or any value or expression) has! This happens at runtime: we cannot actually determine the type ahead of time. Only when the program is executing/all inputs have been supplied.

def find_index(target, names):

for i in range(len(names)):

if target == names[i]:

return i

return "Not found"

target = "Tom"

index = find_index(target, names)

if type(index) == int:

print(grades[index])

else:

print('not found')

If we run this code, the output we see is:

not found

Finally, we have a solution that works! If the name is in the list, the program will print the grade, and otherwise

it will print not found.

One of the reasons we had to go through all these steps is that Python has dynamic typing. The same function or variable may return or contain different types when you run the program with different inputs.

Furthermore, neither Python nor our program help us out by telling us what the possible types are, or that we checked all of them. We have to figure this out ourselves, and remember to do the checking manually.

You can find the code for this option here.

What about Rust?

Let's look at the same problem in Rust. The beginning is similar to the Python code.

fn main() { let names = vec!["Kinan", "Matt", "Taishan", "Zach", "Kesar", "Lingie", "Emir"]; let grades = vec![ 0, 100, 95, 88, 99, 98, 97]; let target = "Matt"; // we need to find Matt's grade }

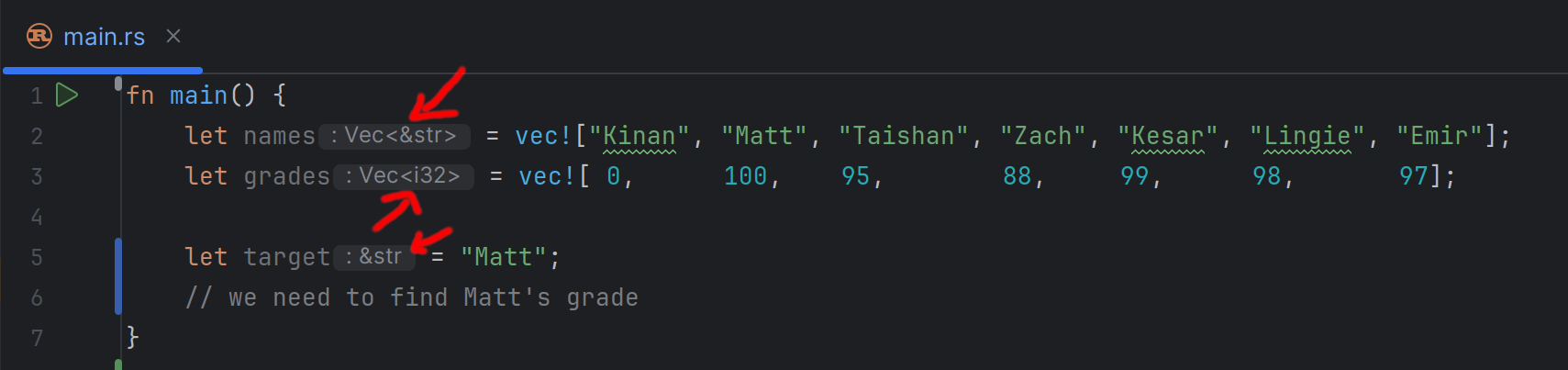

However, we can already see one difference. If you look at this code in a Rust IDE, such as VSCode, you will notice that it automatically fills in the type of each variable. As shown in the screenshot below.

For example, VScode tells us that the type of target is a string (Rust calls this &str, more on the & part later), and the type of grades is Vec<i32>, in other words, a vector (which is what Rust calls

Python lists) that contains i32s in it!

This is quite cool. Not only do we know the type of every variable. We also know information about any other elements or values inside that variable. E.g., the type of the elements inside a vector!

It turns out, we can also write these types out explicitly ourselves in the program. For example:

fn main() { let names: Vec<&str> = vec!["Kinan", "Matt", "Taishan", "Zach", "Kesar", "Lingie", "Emir"]; let grades: Vec<i32> = vec![ 0, 100, 95, 88, 99, 98, 97]; let target = "Matt"; // we need to find Matt's grade }

Furthermore, if we specify types that are inconsistent with the values assigned to a variable, we will get a compiler error!

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { // This should not work: "Kinan" is a string, not an i32. let target: i32 = "Kinan"; }

error[E0308]: mismatched types

|

| let target: i32 = "Kinan";

| --- ^^^^^^^ expected `i32`, found `&str`

This is a consequence of an important design decision in Rust. It follows a strong static typing philosophy, where every variable (and expression) needs to have a single type that is known statically. In otherwords, a type that is determined at compile time before the program runs and does not change if you run the program with different inputs again.

Fortunately, Rust has support for type inference. With type inference, we do not have to write out every type in the program explicitly. Instead, we can often (but not always!) skip the types, and let the language deduce it automatically. Hence, VSCode being able to show us the types in the example above.

Now, let's move on to the next step in the program. We need to implement a find_index function in Rust.

In Rust, function definitions (or more accurately, function signatures) look like this:

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn find_index(target: &str, names: Vec<&str>) -> usize { // the body of the function with all its code goes here. } }

There are a few important differences between this and Python:

- Rust uses

fn(short for function) to indicate a function definition, Python usesdef(short for definition). - Every argument to the function must have an explicilty defined type in Rust. For example, we explicitly state that

targethas type&str(i.e. string). - The function must state explicitly what type of values it returns (if any). This is the

-> usizepart, which tells us that this function return values of typeusize(Ausizein Rust is a type that describes non-negative numbers that can be used as indices or addresses on the computer).

Now, we can try to fill in the function body, mimicing the same logic from Python but using Rust syntax.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn find_index(target: &str, names: Vec<&str>) -> usize { for i in 0..names.len() { if target == names[i] { return i; } } return "Not Found"; } }

We can see a few syntax differences that we already covered earlier in class:

- Python relies on

:and indentation to specify where a code block starts and end (e.g., the body of a function, for loop, or if statement). Rust instead uses{and}. - Rust's syntax for ranges is

<start>..<end>, e.g.,0..names.len(), while Python usesrange(0, len(names)).

However, a deeper difference has to do with the types. The code above does not compile in Rust, and gives us the following error.

error[E0308]: mismatched types

|

| fn find_index(target: &str, names: Vec<&str>) -> usize {

| ----- expected `usize` because of return type

| return "Not Found";

| ^^^^^^^^^^^ expected `usize`, found `&str`

This makes sense. We had already promised Rust that find_index would only return elements that have type usize, but then tried to return "Not Found", a string!

We can try to change the function signature to return strings, e.g. with -> &str. However, this results in a different error: "Not found" is now ok, but return i is not, since i

is not a string (and is in fact a usize).

So, it appears as if we are in a catch 22: no matter what type we chose to specify as the return, we will sometimes try to return a value of a different type.

One quick and dirty fix is to always return usize. So, instead of returning "Not Found", we can return some special number that indicates that the value is not found. We can try returning -1, but we will get a similar error,

since -1 is not a usize (it cannot be negative!). The best we can do is return names.len() and hope that callers manually check this value with an if statement before using it.

fn find_index(target: &str, names: Vec<&str>) -> usize { for i in 0..names.len() { if target == names[i] { return i; } } return names.len(); } fn main() { let names = vec!["Kinan", "Matt", "Taishan", "Zach", "Kesar", "Lingie", "Emir"]; let grades = vec![ 0, 100, 95, 88, 99, 98, 97]; let target = "tom"; let index = find_index(target, names); if index < grades.len() { let grade = grades[index]; println!("{grade}"); } else { println!("Not found"); } }

This code works, although it is not an ideal approach. What if we forgot to add in the if index < grades.len() check? The program would crash with an out of range error. We will see how we can improve it next.

You can find the code for this option here.

Using Option

The main challenge we face is that find_index needs to return some special value/type to indicate not finding something, but only rarely. Rust does not let us return different type dynamically the same way Python does.

So, we need a way to let Rust understand, using types, that there are different cases that find_index may encounter and return.

Fortunately, Rust already has a type builtin that does this. The Option type.

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn find_index(target: &str, names: Vec<&str>) -> Option<usize> { // code goes here } }

This tells Rust that find_index will sometimes (i.e., optionally) return some usize, but it may sometimes not find anything and instead return nothing. Option is a special kind of type (called an Enum, we will learn more about those later) that

can only be constructed in two ways: either, it is a None which indicates that it is empty, or it is a Some(<some value>) which indicates that it has something in it. Furthermore, following Rust's philosopy, the type of that something is known,

in this case, usize.

If we had alternatively said Option<&str> or Option<i32> (or even Option<Option<i32>>), then the type of that something would correspondingly be a string, an i32 number, or another option that may have an i32 number in it, respectively.

Great. Now we can re-write the above function, and if we find no matches, we can return None, while if we find some matching index i, we return Some(i).

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { fn find_index(target: &str, names: Vec<&str>) -> Option<usize> { for i in 0..names.len() { if target == names[i] { return Some(i); } } return None; } }

This is much better!

The last thing we know need to consider is how we call find_index. Previously, we wrote let i = find_index(target, names);, back then VSCode would helpfuly tell us that i has type usize.

Now however, it has type Option<usize>. So we cannot use it the same way as before. For example, Rust gives us an error if we try to do grades[i], since i is an Option! Which makes sense,

what does it mean to look up a value in a list by an index that may or may not exist?

[E0277]: the type `[i32]` cannot be indexed by `Option<usize>`

|

| let grade = grades[i];

| ^ slice indices are of type `usize` or ranges of `usize`

Python cannot do this! Remember how it did not inform us that the index could have been None (in option 2) or a string (in option 3). In Python, we had to manually remember this fact, and manually check which case it was in the code. But, because Rust knows all the types it can remind us of this if we forget.

We can fix our code as follows:

fn main() { let names = vec!["Kinan", "Matt", "Taishan", "Zach", "Kesar", "Lingie", "Emir"]; let grades = vec![ 0, 100, 95, 88, 99, 98, 97]; let target = "tom"; let i = find_index(target, names); // i has type Option<usize> if i.is_none() { println!("Not found"); } else { let value = i.unwrap(); // value has type usize let grade = grades[value]; println!("{grade}"); } }

Take a closer look at the following:

- We can check whether an Option is None or Some using

is_none(). - we can use

.unwrap()to extract the value inside the Option when it is Some.

This code does the job, and you can find it at here.

One reasonable question is what would happen if we use unwrap() on an Option that is None. For example, what do you think would happen if we run this code? (try running it with the Rust playground to confirm your answer).

fn main() { let i: Option<usize> = None; println!("This is crazy, will it work?"); let value = i.unwrap(); println!("it worked!"); println!("{value}"); }

Our program runs, but crashes with an error mid way through:

This is crazy, will it work?

thread 'main' (39) panicked at src/main.rs:4:19:

called `Option::unwrap()` on a `None` value

match Statements

The previous code is almost the ideal approach, but it suffers from one problem. We may make a mistake while checking the cases that an Option (or indeed, other types like Option) may have,

and as a result, call unwrap() when we should not, thus causing an error and a crash.

In fact, unwrap() is really really dangerous! It is almost always better not to use it.

Thankfully, Rust offers us a unique and helpful feature. By using match, we can check all the cases of an Option or similar type, exhaustively and without danger. Here is an example:

fn main() { let names = vec!["Kinan", "Matt", "Taishan", "Zach", "Kesar", "Lingie", "Emir"]; let grades = vec![ 0, 100, 95, 88, 99, 98, 97]; let target = "tom"; let i = find_index(target, names); match i { None => println!("Not found"), Some(value) => { let grade = grades[value]; println!("{grade}"); } } }

So, how does match work?

- You typically match on a value whose type has different cases, like

Option(more accurately, on Enums, which we will explain more in detail later in the course). - You specific the value you want to match on immediately after

match. In the above, we are matching onibecause we saidmatch i { ... }. matchhas a corresponding{and}, like a function, loop, or if statement body.- Within that body, we list the different cases that the value/type may have. These have the following shape:

<case> => <code>,- if the case has nothing in it, we can just write down its name, e.g.,

None. If it has a value, we can tell Rust to put that value in a variable for us and give it a name, for example, ifihas something in it, Rust will put it insidevalue. - the code may be a single statement (like the print in

None) or many statements (line withSome). In the later case, we need to use{and}to specify where the code block starts and ends. - Finally, you must use

,to separate the different cases.

- if the case has nothing in it, we can just write down its name, e.g.,

In my opinion, this is the best solution we have seen. You can find it here.

Why do I think it is the best solution? Because, Rust helps us a lot when using a match statement. Specifically, if we forget a case, Rust will give us a compile error and tell us exactly what case(s) we missed.

For example, imagine we wrote this code (omitting the None case because we forgot):

#![allow(unused)] fn main() { match i { Some(value) => { let grade = grades[value]; println!("{grade}"); } } }

Rust will give us the following error (and in fact VSCode will suggest to add the fix for us!).

error[E0004]: non-exhaustive patterns: `None` not covered

|

| match i {

| ^ pattern `None` not covered

HashMaps

The code we came up with is great for cases where we want to look up one student's grade. However, imagine we needed to look up the grades for several students. Can we use our code to do that?

One suggestion is to manually edit the value of target and re-run the code to look at each student's

grade individually. This works for a handful of students, but will get tedious afterwards.

A different suggestion is to have a vector of targets, and execute our logic for each of them.

In other words, for each of these targets, we first find its index in names using find_index, then print the grade.

This provides the correct but functionality, but it may be slow if we have millions of records and we want to look at thousands of students.

Because, for every student, we have to execute find_index again, and thus loop through all the names again. (We call this a linear time

algorithm or O(n). We will get to the details of this later)

Can we find someway of going through the names only once, and then quickly retrieve as many targets as we want to?

Yes!

We can use a HashMap!

What is a HashMap?

It turns out, the storage layout (i.e., the format of the data) we had is not ideal for these kinds of target lookups, because it uses vectors (i.e. Python lists) whose indices can only be numbers (in a contigous range from 0 to some n).

A HashMap allows us to look up data by an index with a type of of our choosing (called key). So, we can transform the data such that the name of the student is the key to getting

their grade! You have already seen this concept in Python, except Python calls these dictionaries instead of HashMaps!

Here is a Python solution that does this using dictionaries, which you should be familiar with from DS110.

The solution has two steps: First, it inserts the data into the dictonary, which we call map. Second, it can quickly lookup that data in one step using map[<key>], where <key> is the name of the student, e.g. "Kesar".

Importing HashMap

Let's translate that to Rust. The name Rust gives to this datastrcture is HashMap instead of dictionary. We can create a new HashMap using HashMap::new().

HashMap is provided to us by Rust, but we have to import it. In Rust, we do that using use std::collections::HashMap;.

Mutability -- Inserting data into a HashMap

Let's look at the following example using Rust playground.

use std::collections::HashMap; fn main() { let map = HashMap::new(); map.insert("Kinan", 0); map.insert("Matt", 100); }

This code creates an initially empty HashMap, and store it in a variable called map. Then, it inserts two entries to the map. The first has key "Kinan" and value 0, the second has key "Matt" and value 100.

This makes sense. However, if we try to compile or run the code with Rust, we will get the following compiler error.

error[E0596]: cannot borrow `map` as mutable, as it is not declared as mutable

|

| let map = HashMap::new();

| ^^^ not mutable

| map.insert("Kinan", 0);

| --- cannot borrow as mutable

| map.insert("Matt", 100);

| --- cannot borrow as mutable

|

help: consider changing this to be mutable

|

| let mut map = HashMap::new();

| +++

Rust complains about the variable map not being declared as mutable. It turns out, by default, all Rust variables are immutable2.

Definition:

im·mu·ta·ble

adjective

unchanging over time or unable to be changed

"an immutable fact"

This is a philosophical decision on the part of the Rust inventors: one of the main sources of bugs when writing large codebases is to assume that some variable remains unmodified or contain some know value, while having some other, far away part of the code change it, thus causing various bugs.

We need to tell Rust that we map should really be mutable. Thankfully, Rust's compiler error already containers a helpful suggestion, adding the mut keyword.

use std::collections::HashMap; fn main() { let mut map = HashMap::new(); map.insert("Kinan", 0); map.insert("Matt", 100); }

What would happen if you forget to import HashMap and skipped the first line?

Looping through the content of a HashMap

Rust allows us to iterate through the entire content of a HashMap as below.

use std::collections::HashMap; fn main() { let mut map = HashMap::new(); map.insert("Kinan", 0); map.insert("Matt", 100); for (key, value) in map { println!("{key} = {value}"); } }

Note that iterates over the keys and values at the same time. (You may have seen this in Python using .items())

The code above produces this output. Although on your computer, the output may have a different order.

Matt = 100

Kinan = 0

Getting a value from a HashMap by key

But what if we want to retrieve a single value from the HashMap given a key?

Fortunately, this is very easy (and fast!). We can use map.get(<key>). For example:

use std::collections::HashMap; fn main() { let mut map = HashMap::new(); map.insert("Kinan", 0); map.insert("Matt", 100); let value = map.get("Kinan"); }

What do you think the type of value is? Hint: put this code in VSCode and see what it tells you!

Initially, one may think that value will have a numeric type.

However, imagine if we had provided a key that does not exist in the map! E.g., map.get("Tom").

This is the same problem we encountered before!

It turns out, the Rust developers are smart, and they have thought of this, this is why map.get(...) returns an Option<...>!

In otherwords, if we have a HashMap<&str, usize>, get will return an Option<usize>3.

We know how to handle Option types! We can use a match statement as before.

use std::collections::HashMap; fn main() { let mut map = HashMap::new(); map.insert("Kinan", 0); map.insert("Matt", 100); let value = map.get("Kinan"); match value { None => println!("Not found"), Some(value_actually) => println!("{value_actually}") } }

What would happen in Python if you attempt to access a dictornary using a non existing key? e.g.,

map["tom"]?

Putting it all together

We can put all of this together to build our final solution, which you can find here

Understanding this code will help you a lot with homework 2!

Clone this repo to your computer using git (or use

git pullif you already cloned it),

and openmodule_4_variables_and_types/4_hash_mapin VSCode.

Run the code and see if you can predict what the outputs will be.

Also, take a look at what types VSCode shows for the different variables, and see if you can understand why they have these types!

-

If you did not get this reference, you are missing out on one of the greatest movies of all time. Watch it. ↩

-

Change and mutability is a constant in our lives. Unlike in Rust, almost nothing is immutable in reality. If you want to intuitively feel what it means to be immutable or unchanged, listen to this album. ↩

-

In reality, it will return

Option<&usize>, but do not worry about these peasky&s for now. We will go over them later in the course. ↩